The Birth of the ColecoVision: Wishing Upon a Telstar

The Connecticut Leather Company is founded in West Hartford, Connecticut by Russian immigrant Maurice Greenberg in March of 1932, selling shoe repair supplies out of a shop at 28 Market Street. Joining the family business after graduating from Hartford’s Trinity College with a Bachelor of Science degree in mathematics in 1948, his son Leonard champions a move to leather craft kits featuring character licensing from the likes of Disney and Howdy Doody. He also moves the company into vacuum form plastic molding in 1957 and sells off the leather business as their plastic products like sandboxes and toboggans go soaring off store shelves. Organizing as Coleco Industries in June of 1961 and holding an IPO with 120,000 shares available to the public in Sept, by the end of the decade the company is the largest manufacturer of above-ground swimming pools. Lawyer Arnold Greenberg joins his father and brother in 1966, and Coleco sets the stage for its eventual development of toys and video games like the Colecovision by paying $2 million in Oct. of 1968 and acquiring Eagle Toys, a large, Montreal-based maker of popular rod hockey tables that becomes Coleco Canada.

1972 ad for Coleco Swimming Pools

Maurice’s two sons Leonard and Arnold take the helm of Coleco in 1973, Leonard with an eye towards the manufacturing and engineering side as Chairman, and Arnold looking to the finances and marketing as President. In a quest for diversification, Coleco purchases Canadian company Featherweight Corporation, makers of the Alouette snowmobile line, in March of 1972. With a name change to Alouette Recreational Products, Ltd., this division of Coleco Canada diversifies into the off-season with the design and production of its first motorcycle, the AX-125 dirt bike, with disastrous results. A limited run of around 600 bikes, all flagged by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration with multiple defects and subject to a safety recall. After 12 consecutive years posting record profits, Coleco posts a loss in 1973 of $1.2 million. The company divests itself of Alouette Recreational Products in 1975, selling it to Rupp Industries of Mansfield, Ohio. That same year, the success of Atari’s home PONG game opens up a new genre of entertainment, and shows Coleco the path out of possible bankruptcy.

Click button to play a recreation of PONG from 2006

The lynchpin for Coleco’s eventual Telstar PONG-type game console is the AY-3-8500 “PONG-On-A-Chip” LSI (Large-Scale Integration) microchip, released by General Instrument Corp early in 1976. The single videogame integrated chip (IC) had been developed at the General Instrument Glenrothes plant in Scotland in 1975, at the behest of Finnish TV manufacturer Salora Oy for use in a new TV design. As the popularity of the General Instrument PONG game IC spread around Europe in a PAL TV version, work on a NTSC version for North American use is begun in Hicksville, NY. The IC incorporates all of the circuitry needed for a PONG clone, including sound, and offers these games: Tennis, Soccer, Squash and a one-player practice mode of Handball, along with two rifle-shooting games. It also provides character generation for scoring, as well as externally selectable bat sizes and ball speed. Steep or shallow return angles can also be adjusted, and the choice of manual or automatic serving is also available.

Ralph Baer, inventor of the first home video game Odyssey by Magnavox, gets wind of this new “PONG” chip, and tips off his friend Arnold Greenberg. Thus does Coleco become General Instrument’s first customer for the sensational PONG-game silicon. At a cost of $5 to $6 per chip, depending on volume pricing, the rush on this IC is so intense that only Coleco receives their full shipment, early enough to mass manufacture a large enough supply of videogame units for sale through 1976. The release of its Telstar video table tennis unit in May of the year, retailing for half as much as Atari’s console, increases the company’s overall sales by 65 percent; sales of Telstar for 1976 exceed $110 million.

The $49.95 Telstar home PONG clone is ranked at #5 for top-selling Christmas toys in 1976, according to a survey by Toy and Hobby World magazine; by 1979 there will be around 300,000 of the original Telstar unit sold. Coleco has been given a taste of the profits to be had in electronic video games, and it thirsts for more. A 60-day East Coast dock workers strike prevents the company from getting enough circuit boards for the 1977 Christmas season, but Coleco soldiers on in 1978 to produce nine more varieties of the Telstar unit, nearly bankrupting itself again as the home videogame market moves over to programmable, cartridge-based game units. They try to up their game with their own cartridge-based entries like Telstar Game Computer and Telstar Arcade, but the graphics of these machines aren’t much above PONG. With game manufacturers slashing the price of their own dedicated consoles up to 75%, Coleco is forced to dump over a million obsolete Telstar machines onto the market, contributing to a posted loss for Coleco of 22.3 million dollars, with the company holding over $35 million of bank debt.

Telstar Classic video games by Coleco stacked up in a window display in Dublin, California store, 1976

The Third Wave: Making ColecoVision

The success of Coleco’s line of electronic handheld sports games such as Electronic Quarterback and the Head to Head series help keep the company afloat in the late 70’s, with $200 million in sales for the devices posted in 1979, and $400 million for the handheld electronic games industry overall in 1980, a year in which the company’s Head-to-Head Baseball is the #1-selling self-contained electronic handheld game. To handle manufacturing of these games, Coleco has scaled back on its bread-and-butter business of above-ground swimming pools. However, as the toy and games industry is want to do, that year more than 80 companies follow the money and shovel 300 electronic games onto the market. By 1981 the bottom has fallen out of the handheld electronic games market, with Coleco in 1982 posting earnings of $7.7 million, down from $13.1 million the previous year. This leads the brothers to ignore the near disaster experienced with the Telstar PONG clones and fund a new R&D video game division to the tune of $1.5 million, in order to create a next-generation game system, which will eventually become ColecoVision. The team is led by Eric Bromley, who has experience under his belt heading the R&D departments of coin-op companies such as Midway. Bromley’s team is charged to develop a videogame system that will set the standard in graphics quality, performance, and expandability. Bromley himself had done preliminary work in designing and costing a system several years earlier, but the high cost of RAM kept an advanced console out of reach.

By 1981, however, RAM prices have dropped dramatically, so much so that the project is now within range of the target price-point set by Coleco. Bromley and Arnold Greenberg hash out the specs of the new system, giving it the placeholder moniker of ColecoVision until the marketing types can think up a better one. They never do, so the name sticks. At a cost of between $3 million to $5 million, the new system is developed around an 8-bit 3.58 MHz Z80A CPU, with 1K of RAM and 8K ROM. Also on-board is the powerful Texas Instruments TMS9918A video controller chip, giving the system 16K of video RAM and allowing a screen resolution of 256×192. It has the capability to display 32 sprites on-screen at the same time, along with a 16 colour on-screen palette out of a total of 32. Three channel sound via the TI SN76489 sound generator chip is also thrown into the mix for good measure. The ColecoVision cartridges are 32K, the most memory of any system currently on the market.

The ColecoVision is a sturdy looking device, a large black box with two controllers that follow the Intellivision‘s lead by allowing overlays to be inserted over a 12 button membrane keypad. But the system splits the difference between the joysticks of the Atari VCS and the control disk of the Intellivision by having a short, thumb-busting mushroom-shaped stick which proves to be too imprecise for most gamers. At one point in the prototype stage, there are fly-wheel spinners called “speed rollers” included on the controllers, for greater player precision or throttle control in some games. Due to mechanical issues and costing considerations, these are dropped from the design, to resurface again in the later released Super Action Controllers by Coleco. Their omission might also be attributed to the fact that they make the ColecoVision controllers, already outrageously large in smaller hands, even bigger. The machine’s durable cartridges come with connecting boards that are designed to withstand 10,000 insertions into the console cartridge slot, the equivalent of inserting a cart three times a day, every day, for ten years. Probably the greatest promise of longevity of the ColecoVision, however, comes from the large port in the front of the box covered by a sliding panel, called the Expansion Module Interface. Into this maw is where purchasers will plug in the many add-on modules planned to be released for the system. It is Coleco’s insatiable desire to fill this hole that will eventually lead it, and the ColecoVision system, to destruction.

Koming with Kong. Donkey Kong, That Is…

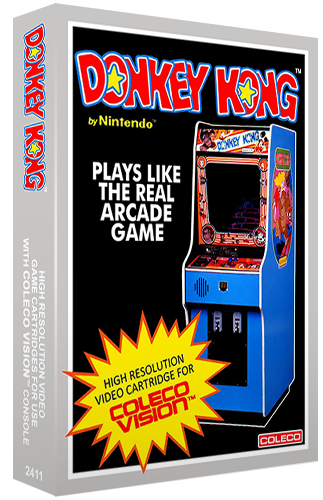

The key to the success of this new machine is to be its pack-in cartridge, an adaptation of the smash arcade hit Donkey Kong. Coleco sends Bromley over to Japan to negotiate the rights, where imposing Nintendo chairman Hiroshi Yamauchi presents him with an ultimatum. Either agree to a pay Nintendo a $2 royalty per cartridge sold and wire a $200,000 advance by the end of the day or risk losing the license to either Atari or Mattel, both of whom are scratching at the door looking to buy. Bromley makes the call to Greenberg and convinces him that the rights to the biggest hit since Pac-Man are within their grasp. A verbal agreement to the Donkey Kong license is made. Bromley later gets a scare when Nintendo informs him they have changed their minds and decided to give Atari the license, but an impassioned plea to Yamauchi persuades the usually iron-willed Nintendo president to stick with the original Coleco deal and later grant Atari only the home computer rights.

ColecoVision Donkey Kong Lawsuit: Coleco v. Universal Pictures

Coleco’s tight adaptation of Donkey Kong for the ColecoVision, realized by about eight months of programming work within the company, propels it to becoming one of the greatest system-sellers in video game history. There will not be a game bundled with a console more effective at showcasing the strengths of the system until 2006 when Nintendo includes Wii Sports with the Wii, perfectly showing users the fun and challenge of its motion-sensing controllers. In 1982, lawsuits are filed against both Nintendo and Coleco by Universal Studios, claiming Donkey Kong and its various ports infringe on their King Kong movie copyright and demand royalties from their sales. This suit is probably helped along by such references in the media of Donkey Kong being “loosely based” on King Kong. A trademark infringement action is also filed, to the tune of over a $100,000,000. With the large sum of money already invested in the license looming in their minds, Coleco cuts a deal with Universal, giving them 3 percent of Donkey Kong sales. Nintendo, however, fights the lawsuit, offering numerous in-court demonstrations of gameplay vs. movie plot. In 1983, Manhattan District Court Judge D. J. Sweet eventually finds for Nintendo, ruling that Donkey Kong has “a totally different concept and feel from the drama” and that “no reasonable jury could find likelihood of confusion”. It is also discovered the fact that MCA Universal themselves had argued in court in 1975 that the King Kong copyright had lapsed into the public domain, in a lead-up for them taking over the rights to produce a remake of the movie, eventually released as King Kong in 1976. Appeals by Universal continue to fall in Nintendo’s favour, from the Federal Court of Appeals all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Second District Court of Appeals unanimously upholds the District Court decision in 1984, stating “the two properties have nothing in common but a gorilla, captive woman, a mere rescuer and a building scenario,” and that “the two characters are so different that no question of fact was presented on the likelihood of consumer confusion.”. When Nintendo countersues claiming tortious interference with licensees and unjust enrichment, in 1985 Judge Sweet finds that Universal has operated in bad faith with spurious litigation and rules that the media company must pay Nintendo $1.8 million in damages and legal fees. The Supreme Court, without comment, refuses to hear an appeal against this judgement on Monday, December 1, 1986, so the penalties against Universal stand. These rock-solid legal outcomes prompt Coleco to eventually file suit to receive a portion of their lost royalties. In February of 1987, an out-of-court settlement has MCA Universal buying $20 million in preferred stock in Coleco, which will convert to 2.2 million shares in the company on the first of January, 1995. MCA promises not to buy any more Coleco stock for the next eight years, pending Coleco’s approval of such a purchase. This deal will put MCA’s equity investment in Coleco as one of the largest, at 23%.

Donkey Kong is also released for the VCS/2600 by Coleco, in early 1983. Game design is contracted out to small engineering and development house Wickstead Design Associates, where Garry Kitchen programs the hotly anticipated title. His version of Nintendo’s arcade hit sells over 4 million copies on Atari’s ubiquitous game platform. Kitchen will eventually end up joining his brothers at Activision.

Click button to play Donkey Kong on the Atari 2600

ColecoVision: That Arcade Quality

Along with Donkey Kong, twelve additional cartridges are announced along with the ColecoVision. While Atari had pioneered the licensing of arcade games for home play with Space Invaders, Coleco makes this a key part of their strategy, aggressively seeking available licenses for coin-op games instead of concentrating on creating original titles. “Arcade games are the backbone of demand in this business,” company president Arnold Greenberg tells The New York Times in November of 1982, “The key to tapping that demand is licensing, which will continue to be a very important part of our operations.”

The potential of ColecoVision and the Greenbergs’ smart moves in the market leading up to the console’s release juices Coleco’s share price on the NYSE, moving from $6.75 per share at the beginning of 1982 to a high of $19 by the middle of July. After a year of development time, the ColecoVision makes its February debut at the Toy Industry Association’s Toy Fair in New York City, and Coleco starts production of the console in July. The ColecoVision sees a slow rollout, with limited amounts of consoles available to retailers first in the Boston and NYC area. Other major markets like L.A. and Chicago, and eventual national distribution, continue through late-summer and fall of 1982, all at a competitive retail cost of $199 at the high end for the unit. In comparison, Intellivisions are selling at the high end for $250, minus a $50 rebate offered by Mattel, and the Atari VCS for $200. The more contemporary Atari 5200 retails at a high end price of $269. The initial ColecoVision units that come off the line at Coleco, some 50,000 of them, end up causing the company trouble. They were released to stores before the FCC gave their approval for their design on Sept. 27. The next month, Coleco agrees to a $2000 FCC fine for what is termed “marketing violations” and will also notify purchasers of the possibility of radio interference from the affected consoles, and how to correct it. Quantities of “launch” games for the ColecoVision are as scarce as the console, especially in the western U.S. Distribution of the powerhouse console outside of North America is handled by CBS Electronics. If one was lucky enough to pick up the console in the official nationwide launch month of August, there wasn’t a single “launch title” game available for purchase for ColecoVision: you only had the pack-in Donkey Kong cartridge to play with. Cosmic Avenger, Smurf: Rescue in Gargamel’s Castle and Venture are the first ColecoVision games to hit the store shelves, in September. These are followed in October by Carnival, Ken Uston’s Blackjack/Poker, Lady Bug and Zaxxon. Mouse Trap and Turbo round out the 1982 ColecoVision game releases, in November. Three other Exidy games are also announced as arcade conversions, but ultimately cancelled: Side Trak, Spectar and Rip Cord.

Click button to play arcade version of Venture. Hit Tab after loading to set controls

The department inside Coleco developing these translations is staffed by around 30 artists, designers and programmers at start up. Once the rights to an arcade game is secured for the ColecoVision, the design team receives an arcade unit that joins its brethren in the “game room”. Lacking any technical source material, the game designers at Coleco must videotape gameplay from the coin-op version for reference while translating the game. The usual timeframe for development of a game at Coleco is three to four months. While the conversions are not flawless interpretations, they are one giant step towards capturing the graphics and game mechanics of the original coin-op for play at home. One fly in the ointment, however, is the seemingly interminable (at least for an anxious kid desperately waiting to play the game) ten-second or so delay between turning on the console with a cartridge inserted, and the game selection screen showing up. This can be chalked up to Coleco wanting to get as many arcade game hits out on their game machine as possible; the initial suite of games for the ColecoVision are programmed in PASCAL, an easier language to create in than the machine language the Z80 CPU natively deals in. While this allows for speedy development, the console must put the brakes on and parse the information from the cartridge at the start of each of each new play session.

Click button to play arcade version of Zaxxon. Hit Tab after loading to set controls

The ColecoVision hits the market in the midst of the public relations war Atari and Mattel are waging against each other. The console is an instant success, with the first run of 550,000 machines selling out by Christmas 1982…. although in the eternal struggle Coleco will fight with its production capacity, 500,000 of these purchases end up backordered into 1983. In the first quarter of 1983, Coleco reports that one million of the devices have been sold in total, along with eight million cartridge sales overall for the company. Coleco’s amazing stock price run has it named the best performer on the NYSE for 1982, increasing to 36 3/4 per share during the Christmas season. Helping the balance sheet along is the incredible reception of Coleco’s electronic tabletop replicas of arcade games, including Pac-Man, Donkey Kong and Galaxian. Even with over 200,000 units coming off the production line by 1982, early in the year, Coleco must withdraw their TV ad campaign for these devices in the NYC area due to a lack of ability to keep up with demand.

Click button to play Coleco tabletop Donkey Kong. Left CTRL button to start, arrows to move and Left CTRL to jump

In front of the slow rollout of Colecovision, Coleco also leverages their arcade game licenses with versions for the Atari VCS starting at the end of July of 1982. Cash ape Donkey Kong arrives on the Atari VCS scene first, along with shooting gallery game Carnival, adapted from the Sega coin-op. Zaxxon and Turbo are scheduled for the following few months. Mousetrap, as well as Smurf Action are to hit shelves by the Christmas season. The unfortunate sounding latter title is eventually renamed Smurfs:Rescue from Gargamel’s Castle.There are also home versions of games for the Intellivision released by Coleco, including a dubious Donkey Kong adaptation released towards the end of August. It takes a little over a year before ColecoVision gamers start enjoying the fruits of third-party game support for their system, with products like platformers Popeye by Parker Brothers in August of 1983 and Miner 2049’er by Microfun in October. Meanwhile, Coleco’s exported games to other systems meet with great success, and the company’s financial performance reflects it. By the fall of 1982 the company’s performance on the stock exchange leads the New York Times to name Coleco as one of its 10 Super Stocks of 1982. Sales revenue for the company has tripled from $178 million in 1981 to $510 million through 1982.

Click button to play Popeye on ColecoVision. Hit Tab once loaded to choose controls

Excellent article. Just discovered your website and thoroughly enjoying it.

Great, thanks! Keep reading and commenting!

What an excellent article. This in one of the few write-ups that really gives readers a sense of what it was like when the ColecoVision was released. You captured it really well. I know, because I got one of these amazing machines when it was first released (thanks Dad).

Yeah, the ColecoVision was quite the machine. I seem to recall playing it so much that I wore out my tendons. The time away from the machine while healing was tough. Later I noticed Nintendo gamers coined the phrase “Nintendo thumb”. I totally understood what they were talking about.

For those that have never tried a ColecoVision, your best bet is the stuff they ported over in-house (as opposed to a lot of the 3rd-party games — which usually sucked). So for a list of gooders, check out:

– Donkey Kong Jr. (Super Donkey Kong Jr. includes all levels from the arcade version)

– Frenzy

– Time Pilot

– Venture

– Zaxxon

– Cosmic Avenger

– Q*Bert

Note: This machine is the same spec as the SEGA SG-1000. So for a similar experience, try the following SG-1000 games:

– Galaga

– Golgo 13

– Hustle Chummy

– Star Force

– Elevator Action

– Exerion

Thanks for the kind words about the article.

As noted in the article, I had a ColecoVision myself, and it was nothing short of a spectacular games console. I know exactly what you mean about straining your hands with the stiff mushroom stick, I’m sure it put a lot of kids’ hands out of commission.

Out of the games you list for CV, Venture and Zaxxon were probably my favourites. I remember really liking Mousetrap too, it was a nice strategic take on all the Pac-Man games that were out at the time. And of course, the Donkey Kong game that came packed with the system was a revelation.

Thanks again for writing!

If you look around you will see people having less time today. So filling the limited spare time with a quick game is what happened (for example during public transport, in a break etc.). You do not have a full blown console with you but you still carry a smartphone or tablet with you… that’s the big difference. I have plenty of games at home for all kind of current consoles but there are a lot I never played and they are still in original cover due to time issues. Last time I want to play with my girlfriend on my PS3 the update of the console itself and the game took 45 minutes alone (!!!). Well not so tell we waited a while and then switching over to watch a movie ;-(

Great article showing the spirit of these consoles. Today Coleco, Intellivison and Atari still have plenty of fans supporting these systems. As old tv’s fade away and people are surrounded by hightech gadgets these old consoles are still attractive if updated: Stereo/Surround sound, AV/Composite video output are state of the art creating new game experience even with old games. If you hear the stereo/surround sound from such an old console you are really surprised how great these games are.

Specially as modern consoles sucks in gameplay and complexity (today you need about 15-30 minute to get warm or update your PS3/P4) quick and easy games are really a runner (for the masses on smartphones/tables). So we may see the dying of dedicated gaming consoles very soon, still living on tables and phones.

I think the latest consoles that were just released as I am writing this, the Xbox One and PS4, really mitigate the issues with long start-up times and having to constantly update them. They have systems in place, such as background updating, that put an end to this kind of thing.

Mobile gaming has certainly come to the fore recently, but I don’t think it will be replacing dedicated game consoles quite yet.