It is pitch dark. You are likely to be eaten by a Grue.

Two hopeless devotees to Crowther and Wood’s computer text game Adventure are Dave Lebling and Marc Blank, part of the Dynamic Modelling Group at MIT. Lebling has already created his own games on the school’s PDP-10 computer, including a take on the venerable Spacewar! by Steve Russell, as well as Maze, a graphical game where two players move around a maze shooting each other. In order to assist with his obsession with paper-and-dice game Dungeons & Dragons, he writes a D&D assistance program to automate bookkeeping for the game. He also collaborates with Blank and another programmer, Tim Anderson, to create a trivia game that users can contribute to and holds a database of over 1000 questions.

Click button to play a version of the original Colossal Cave Adventure, on MS-DOS

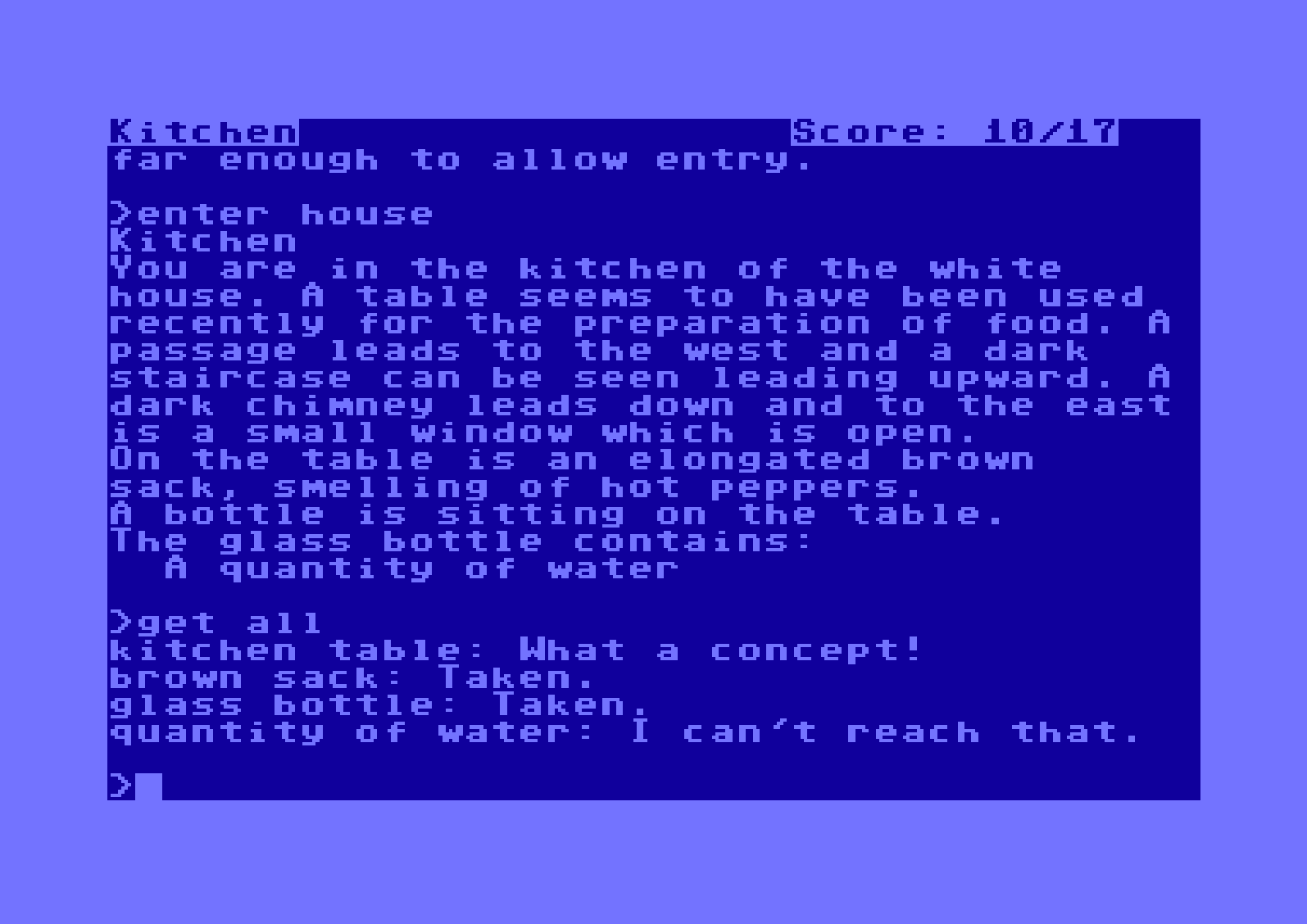

Adventure arrives on MIT’s computer in the Library for Computer Science in early 1977 via the Arpanet, a precursor to the modern Internet. Productivity grinds to a halt as the entire MIT computer community sucks up all the time on the PDP-10s playing it. By May, Adventure has been solved, and Lebling and company feel the need to pursue a more difficult challenge: create an even better adventure game. On the PDP-10 they program a two-word text parser system comparable to the one in Adventure in MDL (Muddle) code, a LISP inspired computer language developed at MIT that counts Christopher Reeve as one of the primary developers, who ends up as vice-president of software of the company later set up around their efforts. They then write a four-room game around the parser system, containing around 10-12 problems to solve. This primordial Zork contains a band, a bandstand, and perhaps as a nod to the election of Jimmy Carter as U.S. President, a peanut room (where outside, the band plays Hail to the Chief), as well as a “chamber full of deadlines”.

This first preliminary experiment is ultimately discarded. With Blank finished with his undergraduate studies and off to medical school at New York’s Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Lebling, Anderson and fellow student Bruce Daniels soon begin work on a more serious attempt. Blank drives up from New York to Boston every weekend to help work on the project. Lebling devises the geographical lay of the land, both upper and lower, as well as composes the expansive descriptions of the locations. More intricate problems to be solved are also sussed out, utilizing a programming technique from MIT’s artificial-intelligence lab that is eventually labeled the Interlogic system, which allows users to input complex sentences as commands, including the use of prepositions and adjectives which allow users to get very specific with their actions. This is opposed to the standard two-word verb-noun parsers found in games like Adventure. Unable to think up a suitable title for the new project, Blank dubs it Zork, a nonsense word used around the Computer Science lab at MIT as a handy (and swear-free) expletive, as well as a placeholder title used for works-in-progress. It is intended that Zork be given a more meaningful title later, although eventually, the name sticks. This borrowing of hacker terms also results in the naming of a large landmass in the Zork games, Frobozz… as in the Wizard of Frobozz, a character that features in the sequel Zork II. The hacker root of the term is “frob”: a small item or thingamabob. When the group finish their first pass at the program in June of 1977, they have a working game about half the size of what eventually becomes Zork I, but in place are most of the trappings of the soon-to-become-legend Great Underground Empire, including the dreaded Grue, a dark-dwelling creature who’s name is borrowed by Lebling from a monster found in the fantasy works of Jack Vance.

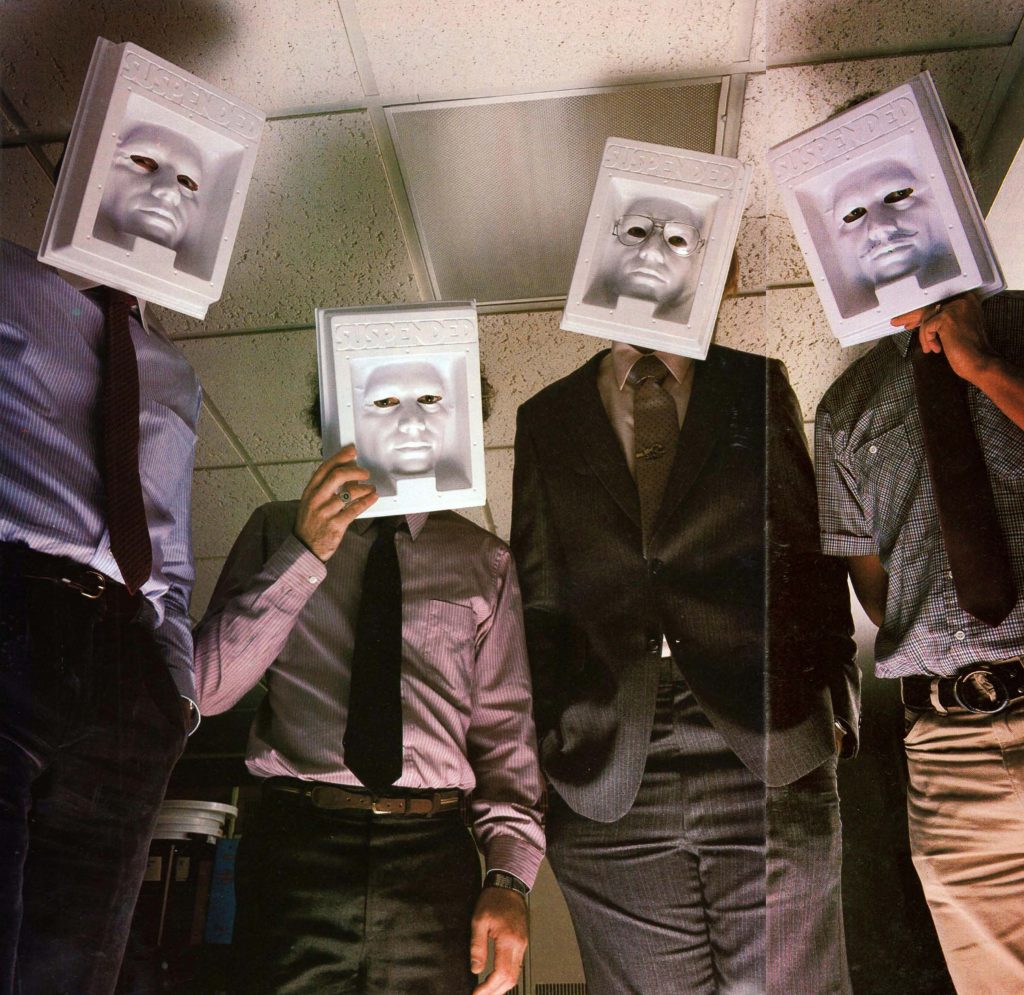

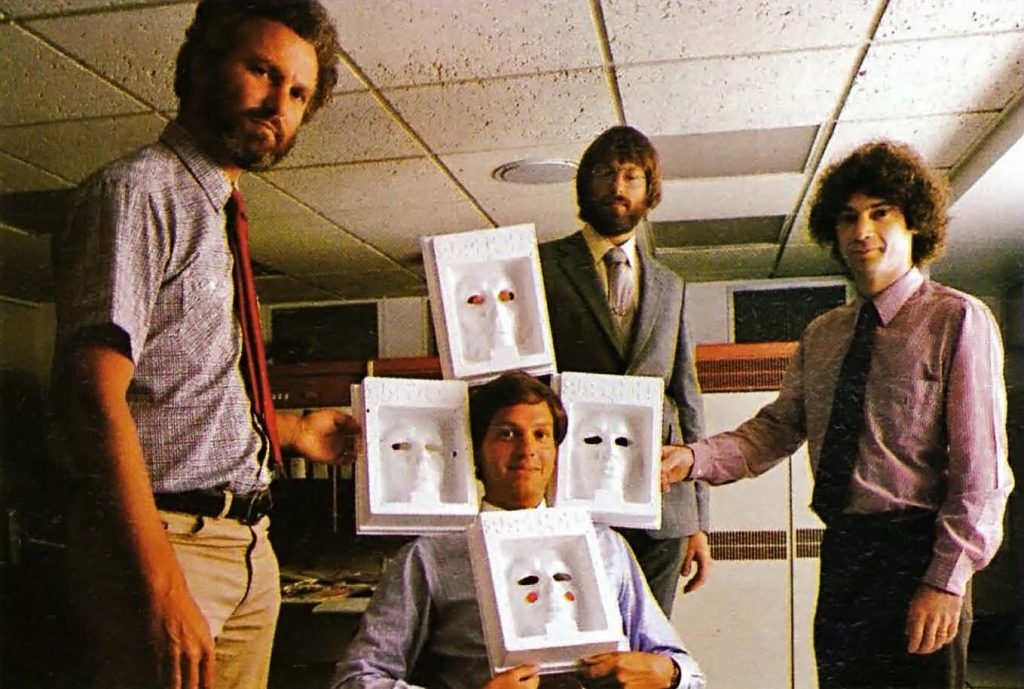

Infocom, 1982 – The most awkward staff photo? Back row, L to R: Chris Reeve, J.C.R. Licklider, Gabrielle Accord, president Joel Berez, Scott Cutler, Michael Berlyn. Front row, L to R: Dave Lebling, Marc Blank, Steve Meretzky.

The game also allows for containers to hold things, NPC characters or “actors” who can wander about and pursue their own agenda, multiple solutions to certain problems and also allows for the passage of time and the triggering of timed events. Sitting on MIT’s PDP-10, Zork (briefly renamed Dungeon before it’s made apparent this conflicts with the 1975 board game Dungeon! by TSR) undergoes a burst of popularity at the school. Hundreds of users become fixated on the game, as well as “net randoms” who log in from outside across the Arpanet. The developers use the many suggestions that pour in for improvements and puzzle additions to the game. Even a multiplayer version of Zork is toyed with, although nothing comes of it. With over 200 rooms to explore and a vocabulary of almost 1000 words, the final puzzle is added to Zork in February of 1979. Around the same time, Dynamic Modelling System lab director Al Vezza, hoping to monetize some of the technology being developed there, creates a company called Infocom, initially operating out of a post-office box in the MIT-adjacent Kendall Square section of Cambridge, Mass.. Also helping form this new venture is Chris Reeve and Stu Galley. They all start off by kicking in a grand total of $11,500 to the company coffers. Realizing the marketability of Zork, Blank and fellow former Dynamic Modelling System denizen Joel Berez, then earning a business degree at MIT’s Sloan Management School, bring Zork to Vezza, and it becomes the company’s first product. As the game hits the one-megabyte size wall in the MDL language, the final mainframe update is made in January 1981.

You see a market here.

Meanwhile, the microcomputer is born. As systems like Tandy’s TRS-80 and the Apple II begin to catch on with the public, the Zork team sees a way that their new company could actually start selling something. Finding the medical profession not to his taste, between the summer of 1979 to spring of 1980, Blank and Lebling work on an ingenious system to move Zork from mainframe to home computer by creating a special language that would run on an emulator, able to operate in any computer environment. The Z-Machine is invented as a non-existent processor that will run the new, compressed Zork Implementation Language (ZIL), a stripped-down version of MDL, which is a machine-independent programming language. Each PC will run its own Z-Machine Interpreter Program (ZIP) to interpret the Z-Machine instructions and run the games. Development is done outside of MIT on a DEC-20, rented from Digital Corporation. The system also allows for ten to one compression of the game data. Even so, Zork is still way too large to fit into the minuscule 100K or so storage of most personal computer floppy discs, so it is split into two separate programs: The Great Underground Empire, Part I and The Great Underground Empire, Part II. A little bit of the legacy program also ends up in Zork III, although that game is mostly newly developed problems and locations. At 70K each, the split-up game data nicely fits on the floppy disks of the early personal computers, with a few extra problems thrown in to round out each package.

You find a Zork.

In 1979, after extensive refinements and bug testing, and sporting a 600-word parser vocabulary, Zork I is deemed finished. Despite all the effort to squeeze Zork into the confines of the burgeoning personal computer market, Infocom makes its first sale of Zork I with its version for the PDP-11. This platform is hardly a growing concern, however, so Infocom starts to shop the micro-computer version around for a distributor. One possibility floated is Microsoft, but upon contacting them Joel Berez learns that they are already selling a version of Adventure, for the TRS-80 and Apple II, via their Consumer Products division. Infocom then finds someone in the neighbourhood: Personal Software Inc., aka Visicorp (makers of VisiCalc, the first spreadsheet program for PCs), of Cambridge, Mass. A pioneering company in the publishing of software developed by others, Zork wasn’t the first piece of entertainment software from Personal Software; The Electric Paintbrush (author Ken Anderson), Bridge Challenger (author George Duisman), Time Trek (author Brad Templeton) and perhaps most notably Microchess, by Peter Jennings, are also put out by Personal Software. Company co-founder Dan Fylstra is already familiar with Zork, having previously played it on a computer while studying at the Harvard Business School. Reaching an agreement with PS in June of 1980, Blank and crew cash their first royalty cheque as Zork for the TRS-80 Model I hits the streets in time for Christmas. In 1980, working for Apple, Bruce Daniels creates a ZIP for the game for the Apple II. Under the Personal Software label, 6000 copies of Zork sell for the Apple II in eight months, and a total of 10,000 overall. Including later re-issues of of the original Zork, Infocom’s flagship product ends up as the top selling recreational software of the time, selling over a million copies worldwide for a wide variety of computer platforms, and undergoes at least 75 version revisions as the company strives to continually correct errors found by players.

Click button to play Zork I: The Great Underground Empire on the Apple II

While considering the release of Part II of Zork, the Infocom group becomes unhappy about PS’s lackluster support for Zork I, and soon learn that Personal Software is planning to drop their entertainment software line while transforming into a new company called VisiCorp. Infocom thusly acquires the rights back for their game and decides to wade into the daunting waters of software game publishing, finding time-shared factory space and an HQ at 6 Faneuil Hall Marketplace: a one-room 8×10 office in the Boston area. Bankrolling the venture is money from the founders, as well as bank loans they themselves guarantee. Bringing on marketing manager Mort Rosenthal, with Joel Berez installed as Infocom president and Al Vezza as CEO, they hang up their shingle and make their debuts as software publishers with Zork II: The Wizard of Frobozz in 1981. The Zork trilogy is concluded with Zork III: The Dungeon Master produced over the course of a year and released in 1982. This is also the same year that published author Michael Berlyn joins Infocom as a game designer or Implementer (IMP). Creating the diabolically difficult Suspended (1983), as well as co-authoring Infidel and Cutthroats with Jerry Wolper, Berlyn would leave the company in 1986 and, among other things, create the Bubsy games for Accolade.

Click button to play Zork III: The Dungeon Master on the good old Commodore 64

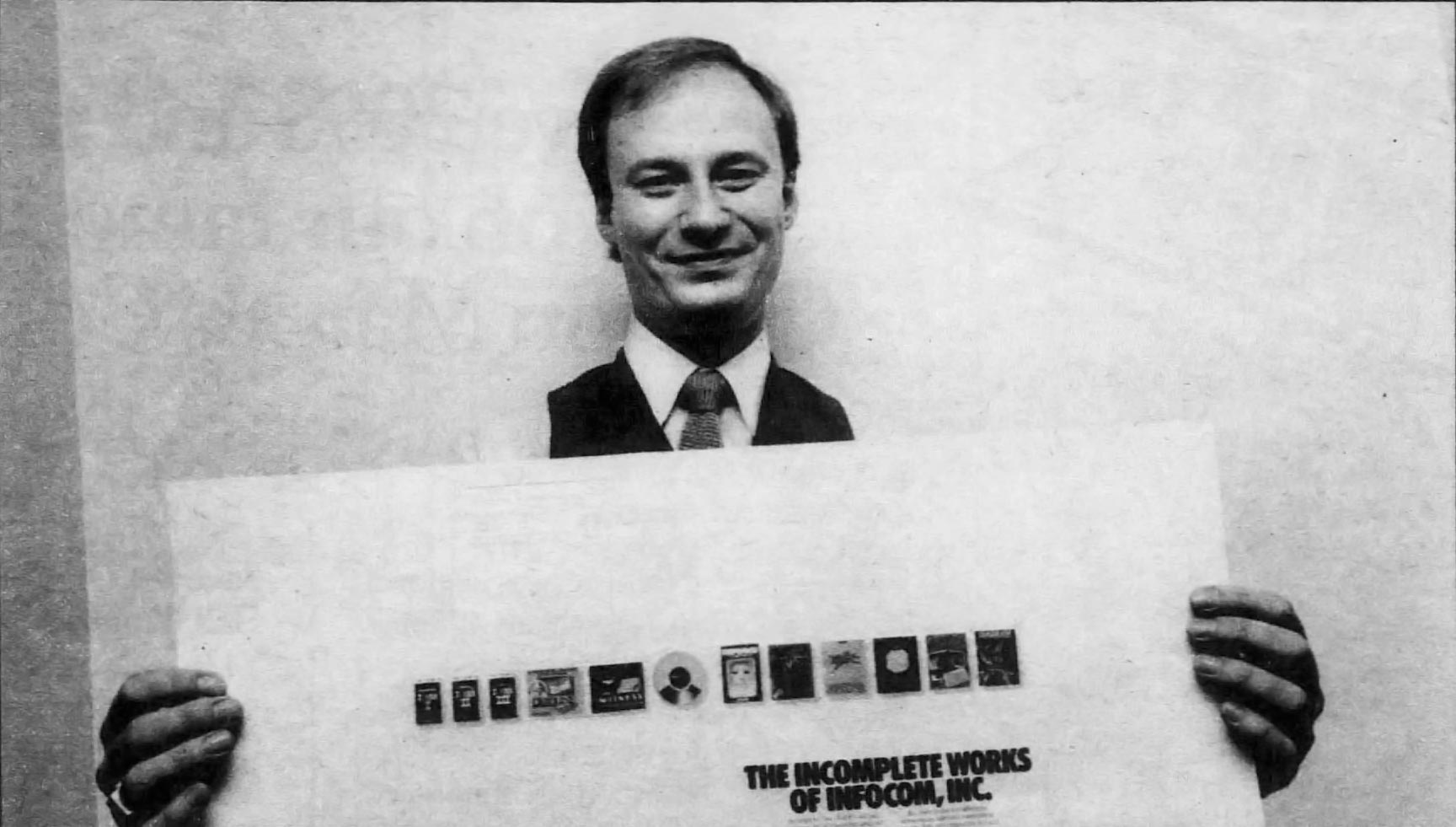

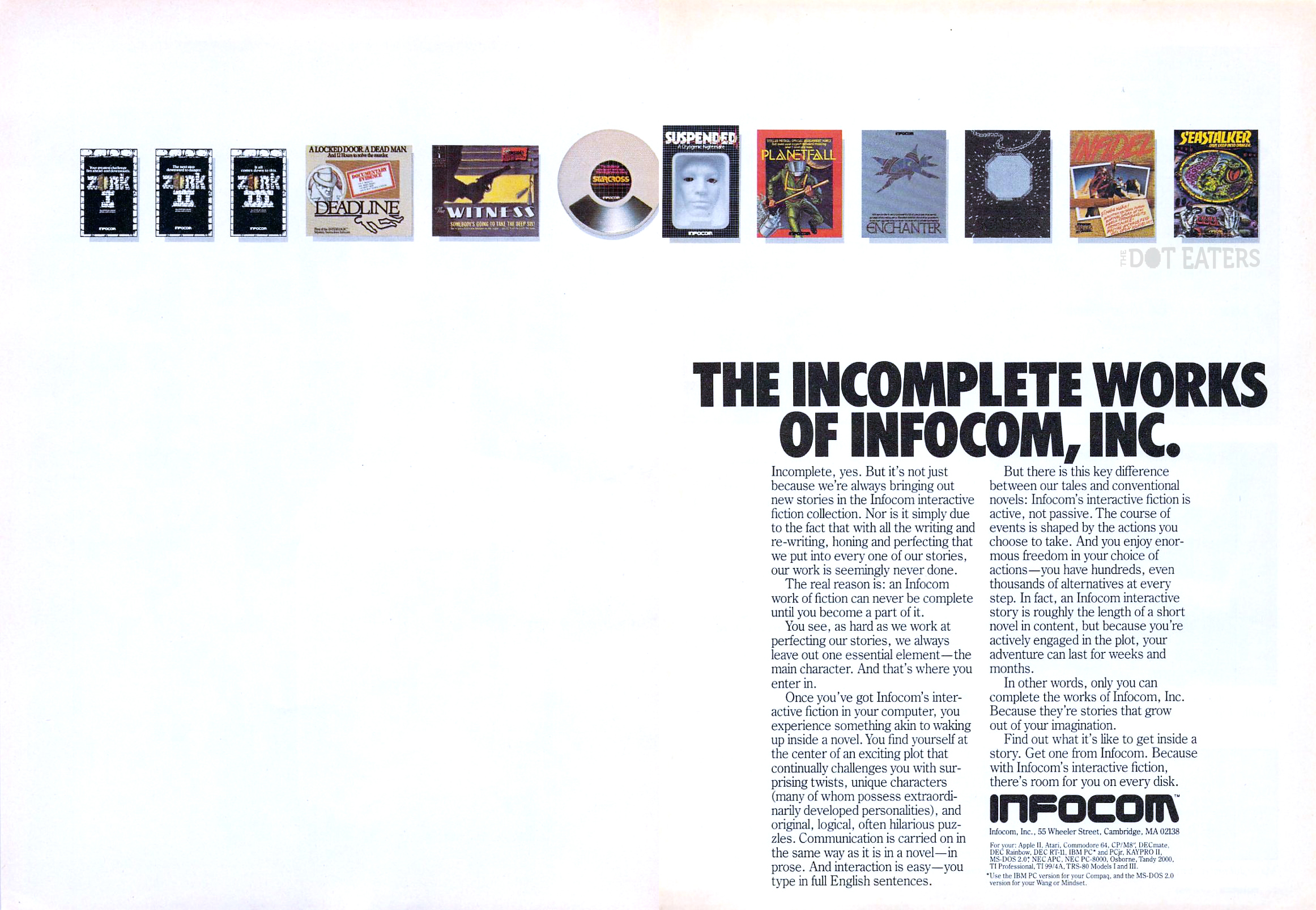

There are ten games based in the Zork world eventually produced in total, and Infocom goes on to become one of the biggest computer game companies in the industry, making over 35 games for over 23 different computer platforms. To give a stark example of the impact Infocom will have on the games market, consider the sales chart for the week of November 19, 1984 from Softsel, an international distributor of computer products. On this influential “Hotlist’, one single company has produced a full third of the 30 games listed under the top recreation products: Infocom. By the holiday season of 1985, the original Zork I has spent an astounding 169 weeks on the Softsel Top 20.

Let me draw a large breath and list the various computers they support, due to the clever Z-Machine interpreter system: Apple II, C64, Atari 8-bit line, DEC Rainbow, DECmate, DEC RT-11, HP 150, HP 110, NEC PC-8000 and APC, IBM-PC, PCjr., KAYPRO II, CP/M compatibles, TI Professional, TI 99/4A, Tandy 2000, TRS-80 CoCo, TRS-80 Models I and II and even a version for the “luggable” portable Osborne I. Another computer model that runs the games is the Apple III… on which Sally Ride, America’s first woman in space, obsessively plays Infocom games. In an interview in People magazine, Ride claims that “Zork is going to drive me to my knees.” In order to produce all this addictive content, a game implementer or imp will usually take from four to six months to create a game, programming it on a DEC 20 computer that is affectionately referred to around the office as ‘Fred’. The development process starts out similarly to the initial creation of a movie screenplay: a treatment is written up, although larger than that of the typical film; usually 10-20 pages of plot, events and characters. One aspect of computer adventure gaming that the IMPS at Infocom obsess on is the world that the player will inhabit in any particular game, and that available puzzles, actions and characters within that world consistently behave and adhere to the corresponding internal rules for that world. The design process is a fairly communal effort at Infocom, with treatments passed around in regular brainstorming sessions to keep things fresh and inject new ideas. As can be imagined with a company that produces fairly complicated text adventure games, testing and quality assurance is a lengthy and arduous process, with a game going through three testing phases: alpha, beta, and finally gamma or a releasable state.

You Feel a Package.

Infocom also attempts some innovation with their packaging, such as the plastic UFO-shaped container for Lebling’s1982 game Starcross, and a large box with a featureless plastic face mask staring out at the customer for Suspended. This game packaging is conceived by the Creative Services department inside Infocom, and designed by external communications services company Giardini/Russell, of Watertown, Mass. They are the ones responsible for many aspects of Infocom’s design motif, including the stony Zork games title font, the copy found in Infocom’s striking advertisements, and what are termed “feelies”. These are tokens, forms, pamphlets and other items included with the games, that serve two purposes: to give players some additional colour to the narrative while playing, and since they often contain critical information on playing serve as a kind of physical copy protection. Infocom pushes this aspect of the included documentation by having the information printed on oddly-coloured paper and folded in strange ways to thwart photocopying.

The company eventually standardizes its outer packaging, mostly due to pressure from retailers who want the company’s products to sit nicely on their shelves. Starting with Cutthroats in 1984, Infocom games are presented in 9″x7″x1″ thin boxes that open like books, to further the idea of interactive fiction. Gamers needn’t worry though: the “feelies” that so enhance the gameplay experience are still present inside. Steve Meretzky’s 1986 adult-leaning SF comedy game Leather Goddesses of Phobos goes so far as to win the award for Best Game Packaging, given to it by the Software Publishers Association. This “adult” interactive adventure starts off as just the provocative title: Meretzky sneaks into a room before an Infocom beer and pizza party and writes the title down on the whiteboard as a joke, inserting it into a list of games that the company has already produced. It becomes a kind of meme with his fellow Infocom IMPs, who when presented with the oft-asked question “So, what are you working on next?”, lacking a more concrete response would simply answer “Leather Goddesses of Phobos!”. When Meretzky finally follows through on his threat to actually make the game, it features ‘Tame’, “Suggestive’ and ‘Lewd’ modes, equating to G, PG and R movie ratings, each selectable in the game by users. Included in the award-winning packaging is a ‘Scratch ‘N Sniff’ card, containing six distinctive scratch areas to which users would be prompted to activate and smell at various points during the game. During development, Meretzky himself would run around Infocom with the samples, pestering employees to guess what the smells were. There is a point and click graphical adventure sequel to the game released by Infocom/Activision in 1992, and forget filling your nose, there is no scratch ‘n sniff. However, the title for it is quite a load for your mouth – Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2: Gas Pump Girls Meet the Pulsating Inconvenience from Planet X! You’ve really got to think that Infocom was making a comment on the elongated subtitles to Sierra’s Leisure Suit Larry games with that one.

Click button to play the completely inappropriate Leather Goddesses of Phobos, IBM-PC version

You find a clue.

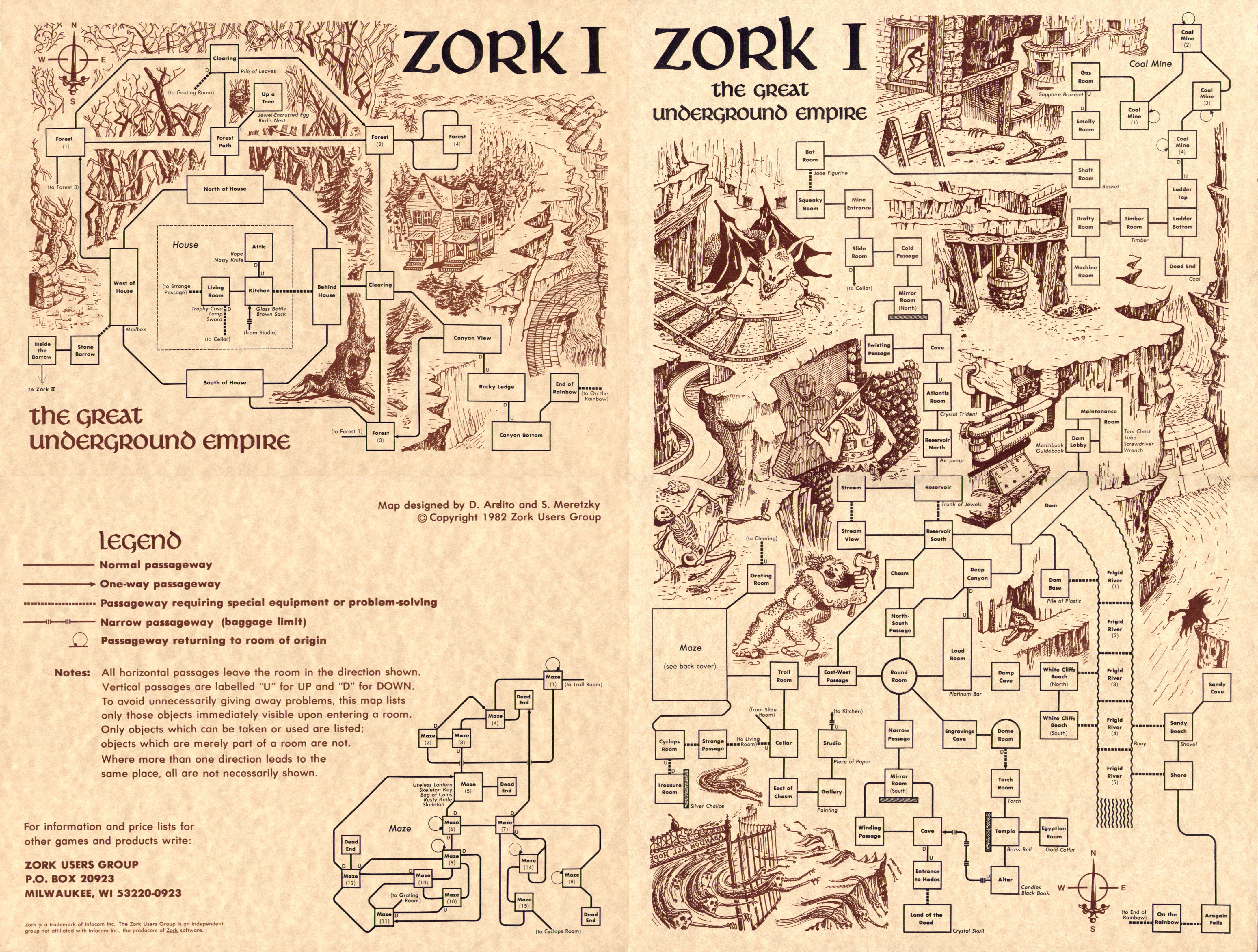

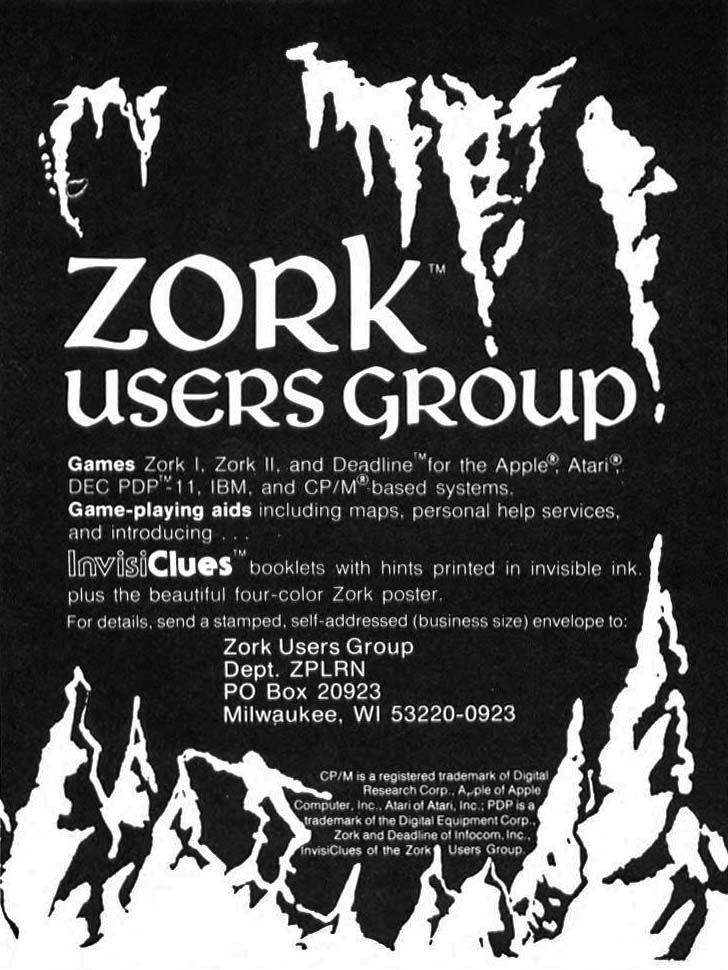

Supporting the growing legion of Zork fans with maps and a 1-800 hint line is the Zork User’s Group, created by Mike Dornbrook in October of 1981. As Infocom’s first paid employee, he had helped his former M.I.T. roomies with play testing Zork at an exorbitant rate of $6/hr while it resided on that institution’s mainframe. Brought in without any previous knowledge at all on computer games to lend a fresh perspective, Dornbrook initially withheld his deepening love of Infocom games from his employers, for fear they would stop paying him to play them. While heading ZUG, initially not officially affiliated with Infocom, Dornbrook is also the editor of The New Zork Times, a newsletter started in mid-1982 and sent out to gamers on Infocom’s mailing list. Upon a not-so-friendly notice from the lawyers from The New York Times, this publication’s name is eventually changed to The Status Line.

ZUG becomes the organization that Infocom refers to when it comes to hints for Zork, and as such Dornbrook is rapidly overcome by phone calls and letters from harried Zork gamers, stuck on one part of the games or another. To alleviate this, he develops the InvisiClues hint books for the Zork trilogy in April of 1982. These offer scaled hints to problems in the game, from vague suggestions to outright answers, written in invisible ink that users can reveal in order of specificity with a special pen packaged with each book. Conceiving of the idea, Dornbrook then calls around the country trying to find a publisher that can print invisible ink… until he comes around full circle to the place of his first inquiries, printing and office supply company A. B. Dick. Re-explaining his needs, they finally realize he is talking about their latent imaging process, where the printed words are hidden until activated by a non-toxic citrus-based marker.

In the initial InvisiClues hint book covering Zork I, there are 175 hints in response to 75 questions, including treasure locations as well as trivia tidbits about the game. The books rapidly become as popular as the games themselves, and after Dornbrook gets his M.B.A. from the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business in June of 1983, he goes to work at Infocom as product manager for entertainment products. Infocom takes over the functions of ZUG in late 1983; by the time of this merging, ZUG has 20,000 members, four employees, and is taking 1000 orders a week for the game and other sundry paraphernalia like the “I’d Rather be Zorking” bumper sticker. InvisiClues books are subsequently made for most every Infocom game of the era, and make their way onto retail shelves as well as available via mail-order through ZUG.

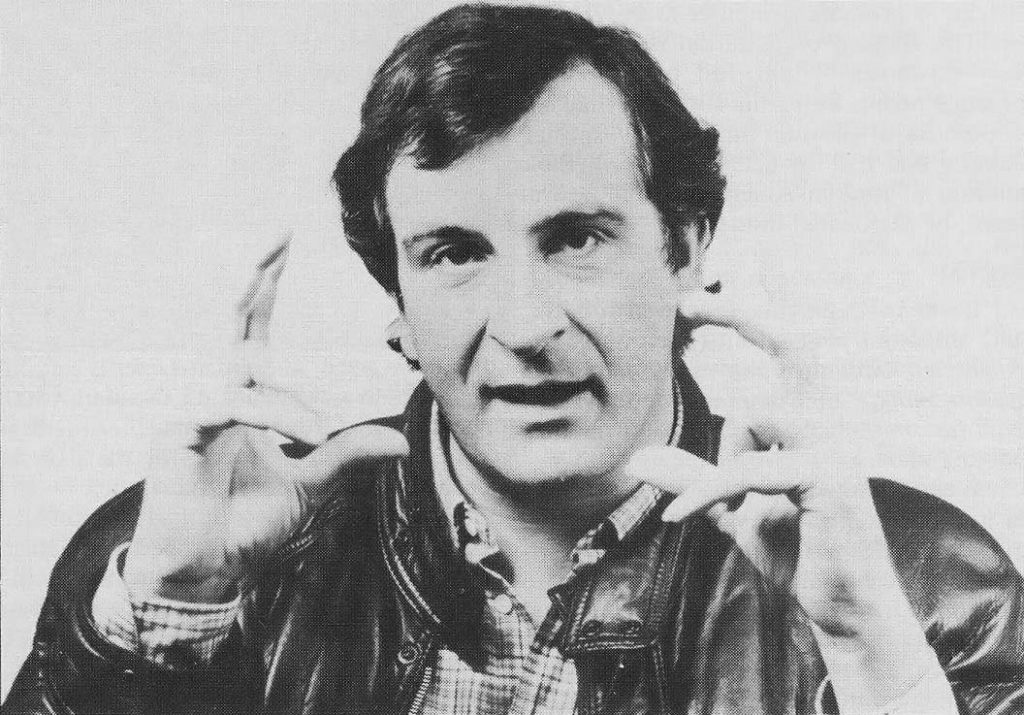

Douglas Adams, circa 1985

A hoopy frood enters the room.

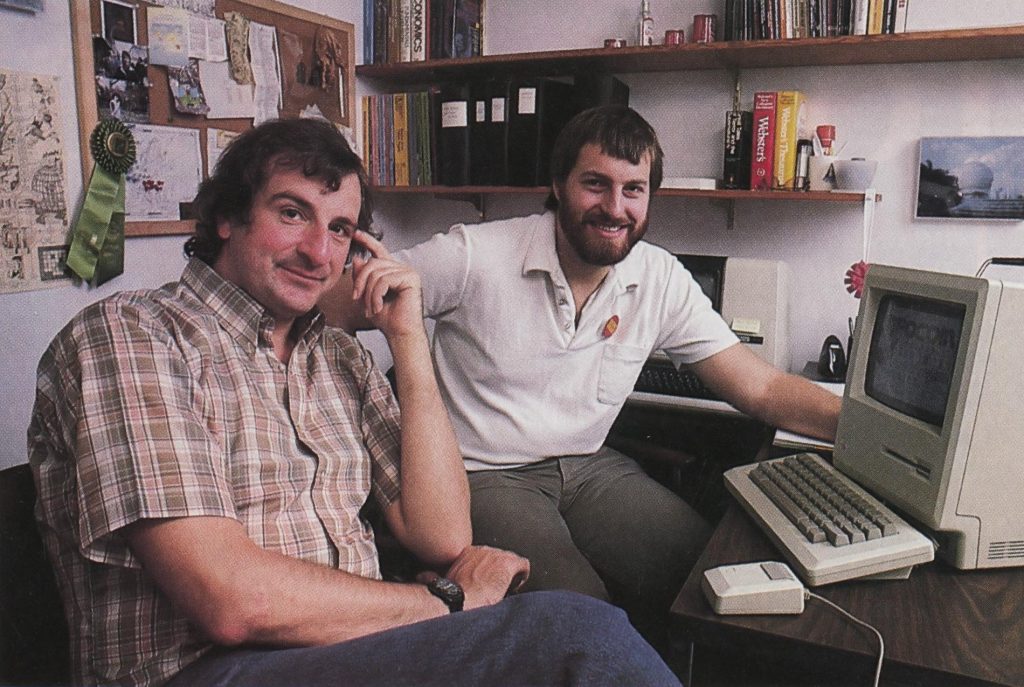

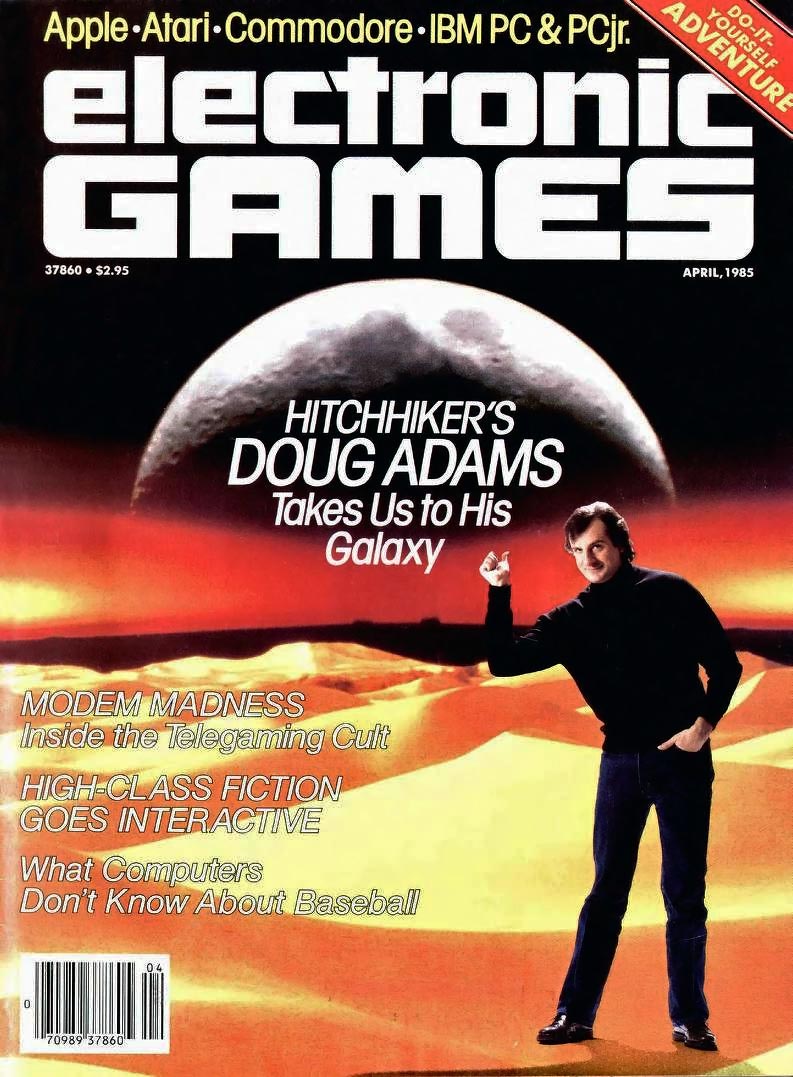

Spawned from his late-70’s cult-favourite BBC radio show, by 1983 The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy book series is a very successful SF comedy trilogy for British author Douglas Adams. As a technophile obsessed with computers, Adams discovers the original Crowther and Woods’ Adventure on then-popular dial-in online service The Source while he is residing in L.A., obsessively playing the game to completion while also trying to get a Hitchhiker’s movie off the ground. Adams then heads to the nearest computer store looking for more adventures. He runs his way through Infocom’s text-adventure library with works like Zork and Deadline and The Witness, but it is only Michael Berlyn’s diabolical Infocom text adventure Suspended that Adams finishes to completion, although with all of them he is immersed in the exceptionally well-written and wildly popular interactive fiction coming out of the company in the 80′s. Adams himself has been approached many times with the idea of turning his most famous work into a video game, but has rebuffed them all. He feels he’s found kindred spirits at the Cambridge, MA game makers, however. That year he is introduced to Marc Blank by humorist Christopher Cerf, a mutual friend. Late in the year, Adams visits the Infocom offices while in town lecturing at MIT. Jumping at the chance of increasing their literary cred with another name author, Infocom signs Adams to a six-game contract in early 1984, with two of the games to be based on the published Hitchhiker’s books. And the company has a natural to pair up with the British humourist: the aforementioned Steve Meretzky.

Meretzky, after graduating from MIT with a degree in Construction Project Management, ran through several jobs in the field, and then was just kind of hanging around by the middle of 1981. Luckily for him, one of the people he hung around with was his roommate Michael Dornbrook, who at the time was testing Zork I and Zork II as Infocom’s first paid employee. Sitting down at the games himself, Meretzky started making his own bug reports, doing such a good job that Marc Blank eventually brings him on to test his mystery game Deadline. By the middle of the following year, Meretzky is a part-time tester at Infocom, and begins formulating his own game on the side, an SF comedy project with the initial working titles Sole Survivor, and then just Survivor. Testing less and writing more, in October Meretzky is bumped up to full-time game writer. His SF game, finally titled as Planetfall, becomes another success for Infocom when released in September of 1983, going on to win multiple awards.

Click the button to play Steve Meretzky’s classic Infocom text adventure Planetfall, on the Apple IIe

The death of Floyd the robot, from Planetfall by Steve Meretzky. Featured on the cover of computer game magazine Softline, 1983. For the heartbreaking final text:

a hiqh-pitched metallic scream.

>Wait.

Time passes. . . . You hear three fast knocks, followed by the distinctive sound of tearing metal.

>Open the door.

Floyd stumbles out of the bio lab, clutching the mini- booth card. The mutations rush toward the open doorway!

> Close the door.

Not a moment coo soon! You hear a pounding from the door as the monsters within vent their frustration at losing their prey.

Floyd is badly torn apart, with loose wires and broken circuits everywhere. Oil flows from his lubrication system.

You drop to your knees and cradle Floyd’s head in your lap. Floyd looks up at you with half-open eyes.

“Floyd did it . . . got card. Floyd a good friend, huh?”

Floyd smiles with contentment, and then his eyes close.

You sit in silence for a moment over the brave friend who gave his life that you might live.

He later follows this up with a sequel, Stationfall. While he creates other games for Infocom, it is the hilarious and touching Planetfall that makes him such a perfect match for Adams, as the game is noted for having an altogether Adams-y sense of humour. Meretzky had not heard of Hitchhiker’s before writing Planetfall, but people testing the game remark how much it reminds them of Adams’ works. When presented with the possibility of collaborating with Adams on a Hitchhiker’s game, Meretzky has said he initially demurred: “When they asked me if I wanted to work with him, I took a long time saying yes; maybe two or three seconds.” As for Adams, he dials in to various Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) in England, trying to gauge user awareness of Infocom. He is met with a small, but rabid, fanbase of gamers.

The Hitchhiker’s computer game’s development process begins in February of 1984, when Meretzky and Adams meet in Boston to hash out their plans, and continues over the next eight months or so. Adams writes passages in England and sends them via computer to Infocom in Cambridge, MA where Meretzky adds additional material and then programs everything into the game using Infocom’s game development system. He then sends completed portions of the game to Adams for review. Connected by two DEC Rainbow computers and modems, the two writers also exchange emails daily, and phone calls weekly. With it not exactly a stretch for Meretzky to adapt to Adams’ writing style, after it is all over both men have a hard time exactly specifying who wrote which part. In June of 1984, with the testing schedule looming in a few weeks and a release window established to take advantage of the Christmas season, Infocom sends Meretzky to England to prod the famous procrastinator Adams to finish his work on the game. At the time, the author is ensconced at his favourite hideaway; the Huntsham Court County House hotel in the village of Huntsham, located near Tiverton, Devon. It is the hope of his book publisher that Adams will focus on the fourth Hitchhiker’s book, titled So Long, and Thanks For All the Fish. Hence the two of them hammer out the remaining material for the game in four days. Returning to the U.S., Meretzky misses the bucolic scenery and relaxed atmosphere of the English countryside as he delves into an intense three-week crunch session to finish the programming of the game. After a brief testing phase, Adams does some rewrites of the material according to feedback from game testing results.

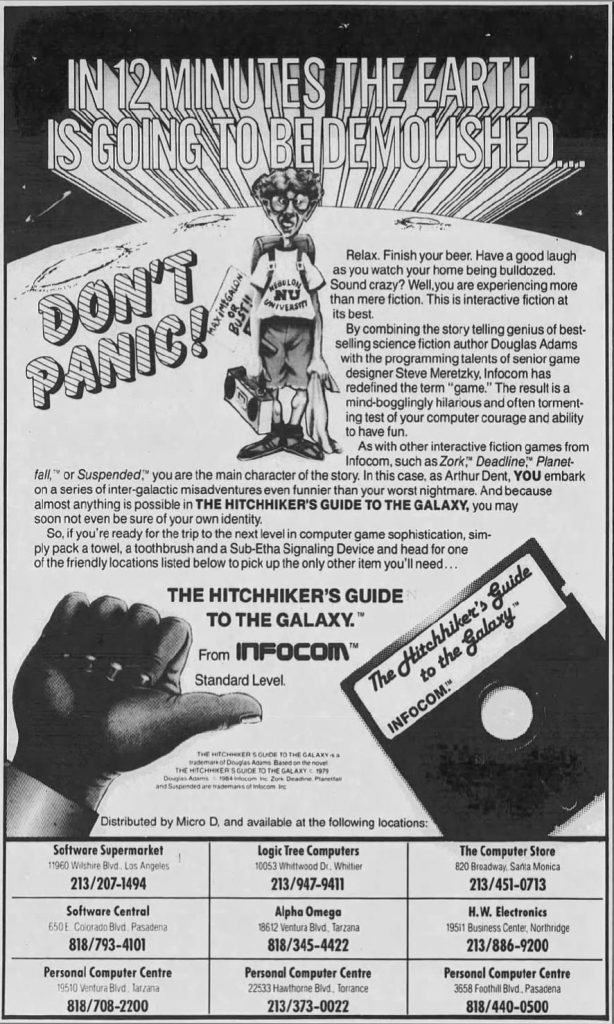

Released in October 1984, the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy text adventure becomes an immediate success, selling over a quarter of a million copies. Described by Adams as “inspired” by his book rather than an adaptation of it, the game rides the top of the game charts for months, and is Infocom’s second-best seller, topped only by the company’s Zork. By the end of 1984, it has sold 350,000 copies.

Click button to play Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy on the Commodore 64. Don’t believe the lies!

While faithful to the tone of the books, the game revels in breaking as many of the cardinal rules then established in interactive fiction, including outright lying to the player about available directions to travel in, and even what the player is able to see. In fact, Hitchhiker’s is cruelly obtuse, often requiring players to initiate actions outside of any offered information in the game, and at many times only those with knowledge of events in the books would know what to do. It also appears to be a favourite torture of Adams to let you miss some critical piece of equipment during a scene that would cause the game to dead-end later, with no recourse but to reload a save or replay the game. It also offers long, drawn-out sequences, such as the maddening Babel Fish Puzzle, which gains such notoriety that Infocom itself sells an official I Got the Babel Fish t-shirt. The ultimate goals of the game are unclear, except perhaps to retain your sanity as you play it. Hitchhiker’s is so hard, in fact, that even reviewers in computer game magazines are stumped; Jack Powell and Michael Ciraolo, reviewing the game for Antic magazine in its May 1985 issue, openly admit that they were stuck at a puzzle that delayed publication of their review for a month, and they STILL hadn’t completed the game. At times it seems that Hitchhiker’s was purposefully created as a ploy by Infocom to sell more of their Invisiclue hint books.

Puzzle brutalities aside, the game is an interesting extension of the Hitchhiker’s cannon, extending the book metaphor by featuring the literary device of footnotes that offer asides to the action. The actual Hitchhiker’s Guide is an inventory item in the game and features plenty of articles for the player to consult about. The game also takes a philosophical bent, with “no tea” being an inventory item that the player at one point drops after getting some real tea, and is eventually able to carry both tea and no tea at the same time after some synaptic calisthenics. Random events also serve to keep subsequent playthroughs interesting, and the game is also strangely obsessed with fluff of all kinds. So much so, that the feelies that accompany the game packaging include a bag of pocket fluff, as well as perpetually-darkened Peril Sensitive Sunglasses and a microscopic battle fleet (empty ziplock bag). Unfortunately, the accountants at Infocom are not froods who know where their towel is, as the one planned to be included in the box is costed out of the design. Considering all the ephemera that IS included with the game, though, Hitchhiker’s game is no fluff-piece, but a fitting entry to Guide lore. Soul-crushingly frustrating, but fitting none-the-less.

NEXT WINDOW PLEASE

With the resounding success of the Hitchhiker’s game, it’s no wonder that Infocom is anxious for a sequel. Milliways: The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, based on the second Hitchhiker’s book by Adams, is tee’d up for development, with Adams planning to collaborate with friend and English author Michael Bywater on the project. The problem is that Adams is tired of producing sequels of his Hitchhiker’s material, and suggests instead Bureaucracy, an original game idea based on his real-life frustrations at trying to get his bank and utility companies to acknowledge a change-of-address after moving apartments in London. Infocom, having signed Adams on the idea that he would be bringing his popular Hitchhiker’s material with him, balks at the idea, but eventually, comes to terms with producing an original work with Adams.

Outside of forming the initial idea, however, Adams begins to let the project be bumped by other commitments, and so he eventually hands it over to Bywater to finish. In line with Adams’ initial concept for Bureaucracy, the game has the protagonist jumping through hoops to accomplish the most simple tasks, such as withdrawing money from a bank, purchasing an airline ticket or even just ordering food at a restaurant. The ultimate goal, of course, is to get the bank to recognize a change-of-address card.

The game starts, in true bureaucratic form, by having the player fill out a “software license application” form for the game, providing humorous comments as you fill in lines such as your last name, name of boy/girlfriend, and whether the player is male or female. The game will then reference you using the opposite of the information provided, such as calling you Mr. if you put your sex down as female. Throughout the game, the blood pressure of the player is shown on the top right of the screen, rising as annoyances occur or when the player enters an invalid command. It is possible to die of an aneurysm if the player lets this rise too high without taking a cooling off period. Following a lead from Hitchhiker’s, the game throws many random events at the player.

Click button to play Douglas Adams’ nightmarish Bureaucracy, on MS-DOS

Unfortunately, the prose in Bureaucracy is a bit twee, and the humour often comes off as forced. It moves from ridiculous to just plain stupid for convenience sake, offering up the idea of having to give a long, drawn-out food order in a restaurant to the waitstaff multiple times as the height of hilarity. It is less the Kafkaesque, paranoid nightmare it wants to be than an annoying, tortuous exercise in tedium. That might be the ultimate point of Bureaucracy, but does that make it an enjoyable game to play?

Bureaucracy is Adams’ last game for Infocom, although he does continue in the medium, assisting on projects such as LucasArt’s movie tie-in Labyrinth: The Computer Game. Adams eventually forms a digital media company along with Richard Creasey and Robbie Stamp in 1996 called The Digital Village, and from this partnership comes the extravagant CD-ROM adventure game Starship Titanic, again joined by his friend Michael Bywater, among others. In 2001, at the age of 49, Adams is rudely taken from us after suffering a heart attack.

This passage leads to a dead end.

Click to play the game that helped sign the death warrant for Infocom text adventures: King’s Quest

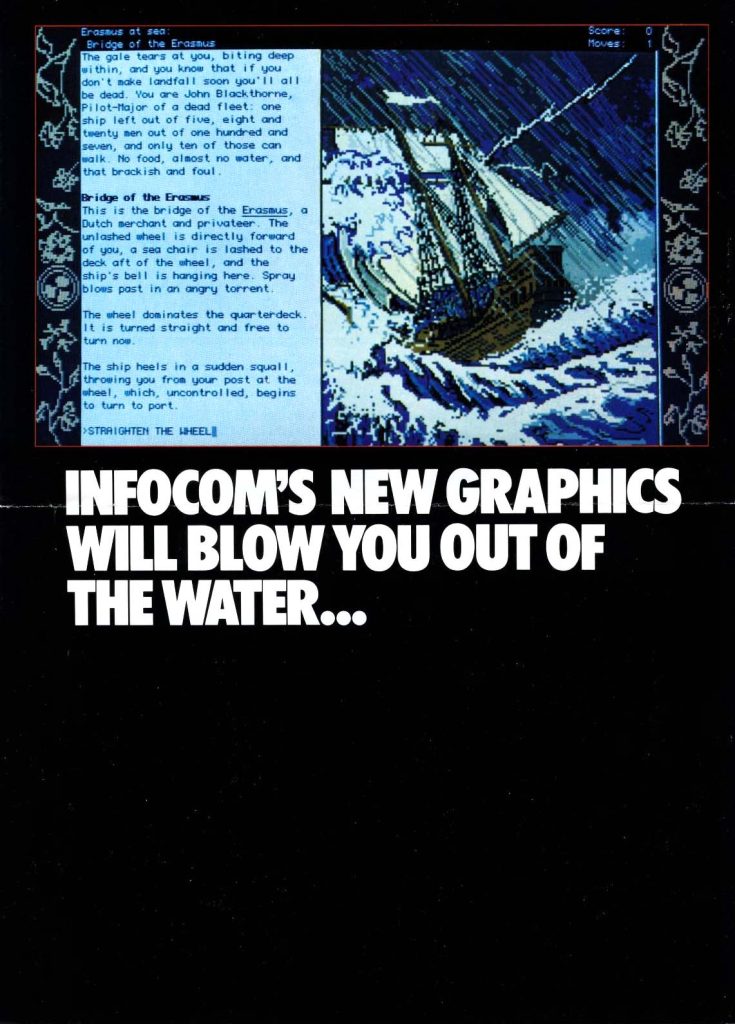

In 1984, the same year as the release of Infocom’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy game, Sierra On-Line drives what is perhaps the first nail into Infocom’s coffin… their release of the spectacular graphic adventure King’s Quest. It ushers in faster processors, more advanced graphical capabilities, and more RAM, leading to improved graphics and sound supplanting text as the canvas of adventure game creation. Meanwhile, a lot of resources at Infocom are poured into a new Business Products division, with a new programming staff and marketing team to support Infocom’s deviation from their comfort zone of sophisticated adventure games and into business software… and what is perhaps the second coffin nail. Two years in the making, the new division produces powerful and streamlined database software Cornerstone, announced by Infocom on Nov. 1, 1984, and released the following year. Optimistic with promises from five of the top software distributors around the country to carry their product even before it is released, Infocom prices its database program at $495, but sales eventually stagnate and not even an eventual slashing of price down to $99 by 1986 can persuade the business community to buy volume software from a “games company”. While the program is as user-intuitive as you’d expect a product from Infocom to be, it is also cumbersome and ponderously slow. Cornerstone fails to catch fire, selling only about 10,000 copies, and the company finds itself in financial hot water. Announced on February 19, 1986, Infocom is purchased by Atari 2600 pioneers Activision for 7.5 million, paid mostly in company stock options and debt acquisition. Although Infocom management changes, with Joel Berez taking over the CEO role from departing founder Al Vezza, the announcement does pledge that the two businesses will remain separate and that Infocom will retain its facilities in Cambridge.

Over 1987 Infocom grosses $10 million, with over two million units sold of the original trilogy of Zork games alone. After purchasing the company, Activision wastes no time in bundling boxes of the classic games together in collections Zork Trilogy, Enchanter Trilogy, Science Fiction Classics and the Classic Mystery Library. That year the company also releases Beyond Zork, created in a little over a year by Brian Moriarty. This is Infocom’s first step in the evolution of their text adventure paradigm. Tasking players to embark on a quest for the magical Coconut of Quendor, Beyond Zork is the company’s first game with a graphical user interface, along with an onscreen map that changes as the players move from room to room. It also explores the realm of the role-playing game by assigning percentage statistics to seven attributes: Endurance, Strength, Dexterity, Intelligence, Compassion, Luck and Armor Class. Raising these skills to a certain level is required to solve certain puzzles. The player also has a choice of choosing between a male and female character, who is referred to personally throughout the game.

Click button to play Infocom’s evolution into graphics, with Beyond Zork, for MS-DOS

Besides the onscreen, updating map, the “enhanced mode” features of the game include mouse support for computers that have one, for clicking on the map to move to adjacent areas. Users can also pin information to a window on the screen, allowing them to constantly keep track of such info as their inventory or the current room description. While the on-screen mapping and extra visual flourishes with the text are designed to make the text adventure easier to play, Infocom purists can revert to the no-nonsense display style of previous games if they prefer. There is also the ability to assign command strings to the function keys of your computer, and even the option to rename characters and objects. To make things even less frustrating while wandering around the Kingdom of Quendor, an undo function is available, even if the last command has resulted in your untimely demise. Be warned, however: if, when you perish, you happen to type out any popular swear words, you’ll take a -1 to your Intelligence rating. The geography and items (and their uses) are randomized from game to game, in order to keep players on their toes and increase the replayability of the adventure.

- Infocom, buffeted by a sea of improving computer graphics, introduces the novel idea of pictures, 1989

While still a purely text game, also new is Infocom’s venture into the romance genre, with Plundered Hearts, released in 1987. The implementor on the project is Amy Briggs, who works her way up from play tester to game designer, although Hearts is her only full game at Infocom. It is also the company’s first game that features a specifically female lead. Beyond Zork is followed up the next year by Zork Zero: The Revenge of Megaboz, designed by Steve Meretzky. Created over the course of 18 months, the game continues the march to integrated graphics with an onscreen map, visual puzzles to play and graphical flourishes around and inside the text prose.

Click button to play Infocom’s continued transition into graphcs, with Zork Zero

Despite Infocom’s continued attempt to catch up to a rapidly changing entertainment software landscape and integrate more graphics into their games, the company continues to accrue losses to the tune of an average of $200,000 per fiscal quarter between 1987-1989. In May of 1989, Mediagenic, formerly Activision, announces that Infocom will be leaving their long-time digs in Cambridge the next month and moving to the mother company’s headquarters in Menlo Park, Ca. Only five of the remaining 26 employees at Infocom elect to move with the company. Joel Berez, for his part, had already left his position as Infocom company president in the summer of 1988, replaced by Joe Ybarra.

Click button to play the full-blown graphical point and click adventure game Return to Zork

In 1993 Activision gives the GUE the full graphical treatment in the rather shaky Return to Zork, with over 20 hours of digitized footage of professional actors shot for the production, all spouting real dialog: a demonstration of the multimedia bells and whistles now available to game makers through the emerging CD-ROM market. In 1995 Activision revisits the roots of Infocom by releasing the original games on the format, in a series of collections loosely grouped by genres, such as Adventure and Mystery. 1996 sees the release of Zork Nemesis: The Forbidden Lands, with the 360 degrees “Z-Vision” graphics engine and an improved user interface. The game does, however, eschew the humour that made the original Zorks great for a more darker tone. Activision also takes a 180 degree look backwards the same year, with yet another mining of past glories. This box contains 33 of them, in fact, in a gathering of Infocom games titled Classic Text Adventure Masterpieces. After Nemesis, Activision gets back on track with Zork: Grand Inquisitor in 1997, similar in mechanics as the previous instalment, and a star-studded affair that features no less than Battlestar Galactica/The A-Team star Dirk Benedict, among others (Rip Taylor!). With Inquisitor, the Zorky humour is back in full force.

The passage ends here.

Befitting its literary aspirations, the Zork universe is also fleshed out in tree-killer book form, starting with a series of “Choose-Your-Own-Adventure” type books, the likes of which influenced Interactive Fiction to start with. Here referred to as “A What-Do-I-Do-Now Book”, they are authored by S. Eric Meretzky, a more fancily titled and aforementioned Steve Meretzky. They are named Zork: The Forces of Krill (1983), Zork: The Malifestro Quest (1983), Zork: The Cavern of Doom (1983), and Zork: Conquest at Quendor (1984). As expected, readers are presented with perilous situations and given a choice of action which results in being directed to a page in the book where the outcome is described. These are followed by full novel tie-ins published by Avon Books between 1988 and 1991. First, comes 1988’s Wishbringer, a novelization of the original Infocom game from 1985, by Craig Shaw Gardner. The novelization of Enchanter, Infocom’s 1983 release, comes from Robin W. Bailey in 1989. Standalone stories The Zork Chronicles (George Alec Effinger, 1990) and The Lost City of Zork (Robin W. Bailey, 1991) continue to flesh out the ever-expanding world of the Great Underground Empire.

There’s been a lot of fallout from Infocom and the dozens of games produced by the company, but the most enjoyable might be the graphic point-and-click adventure games made by Legend Entertainment, founded by former IMP Bob Bates, who was one of the few outside freelance programmers utilized by Infocom: in Bates’ case near the end of the reign of Infocom. Bringing in Steve Meretzky, Legend produces at least one unmitigated classic – Spellcasting 101:Sorcerers Get All the Girls, released in 1990. ![]()

Sources (Click to view)

Page 1 – It is pitch dark. You are likely to be eaten by a grue.

The Development of Zork

Compute!’s Gazette, “Inside View – Marc Blank”, by Kathy Yakal, pgs. 64 – 66, Vol.1 No.4, Oct 1983

Gerrard, Mike. “Bureaucracy Has Got Llamas, Rambo-like Paranoid Schizophrenics, Reagan, Gorbachev and Your Bank.” The Guardian [London, England] 26 Mar. 1987: 9. Newspapers.com. Web. 15 July 2021. “You would look at these PDP-10 computers, which were all time-sharing machines, and there would be 12 people logged in and everyone of them playing Adventure. What happened was that though we all loved Adventure, we decided ‘We can do better than that’.” The “We” included Christopher Reeve, now Infocom’s vice=president of software development and one of the primary developers in 1970 of a programming language with the endearing name of Muddle. ;When Zork 1 was eventually published it was distributed for Infocom by Visicorp, of VisiCalc fame, and sold just over 10,000 copies, fairly typical for a game in the US then.

The New Zork Times, “The History of Zork – First in a Series” by Tim Anderson, pgs. 7, 11, Winter 1985. “In early 1977, Adventure swept the ARPAnet.” “When Adventure arrived at MIT, the reaction was typical: after everybody spent a lot of time doing noting but solving the game…” “By late May, Adventure had been solved…” Marc and I, who were both in the habit of hacking all night, took advantage of this to write a prototype four-room game. It has long since vanished. There was a band, a bandbox, a peanut room (that band was outside the door, playing ‘Hail to the Chief’, and a ‘chamber filled with deadlines'” “‘Zork’ was a nonsense word floating around…” “We tended to name our programs with the word ‘zork’ until they were ready to be installed on the system.” Retrieved from the Internet Archive, NZT collection, Sep 23 2015.

Ceccola, Russ. “Adventures at Infocom.” Commodore Jan. 1988: 70+. Print. Adventure appeared on M.I.T.’s ARPAnet in the Library for Computer Science about a decade ago.

The New Zork Times, “A Zork by Any Other Name”, pg. 3, Winter 1984. “Blank chose Zork, a nonsense word commonly used at the MIT Lab for Computer Science as an all-purpose interjection” “…the original Zork had well over 200 rooms, a vocabulary of nearly 1000 words…” Retrieved from the Internet Archive, NZT collection, Sep 23 2015.

Dyer, Richard. “Masters of the Game.” The Boston Globe 06 May 1984: 12+. Newspapers.com. Web. 15 July 2021. Infocom was founded just under five years ago by eight young men at MIT who kicked a few hundred dollars each into their new company, which operated out of a post-office box in Kendall Square. ;”Actually,”, says Blank, calming down, “it’s [Zork] just a nonsense word. There are all kinds of words like that that hackers tend to use – words like ‘Frob.’ Frob means thingamajig….” ;”That’s why we named the wizard in Zork II the Wizard of Frobozz.”

Adams, Roe R., III. “Exec Infocom” Adventures in Excellence.” Softalk Oct. 1982: 35-40. Softalk V3n02 Oct 1982. Internet Archive, 30 Apr. 2015. Web. 08 Dec. 2015. That’s where Lebling comes in. “I’m in charge of the purple prose; and I did the geographical design of Zork I.” By June 1977, the first version of the mainframe Zork was finished. “So how did I (Blank) write Zork, in Boston, From New York? Easy. I used to drive up every weekend and work with Tim on it.” Berez, at that time, was in the Sloane Management School at MIT earning his business degree. They took the idea to Vezza, who agreed to let Zork be Infocom’s first venture. From the summer of 1979 to the spring of 1980, Blank wrote the compiler and Lebling wrote the assembler or the new language. During this time, Zork for the micro was being developed independent of MIT on rented space on a DEC-2 from Digital Equipment. “We talked to Dan Fylstra from Personal Software about Zork. Tuned out that when Dan had been in business school in Boston, he had played Zork on my computer while doing a thesis. So he knew what Zork was all about.” Personal underwent a corporate metamorphosis into VisiCorp. The new image involved VisiCorp’s dropping all its game lines and concentrating on business programs, so Infocom took back the rights to market the Zork line. “We took our first office last September in the Faneuil Hall Marketplace in Boston. It was only one room…”

Katz, Arnie. “Inside Gaming.” Editorial. Electronic Games Aug. 1983: 84-86. Electronic Games Magazine (August 1983). Internet Archive. Web. 06 Feb. 2016. “The original version [of Zork] had 10 or 12 individual problem situations,” says Blank, “and input was in the traditional verb-noun format since we used a two-word parser.”

Electronic Fun with Computers and Games, “EF’s Gamemakers: Who Dunnit?”, Marc Blank interview by Randi Hacker, pgs. 39-42, 94-97, Oct 1983. “…a language and a system that would enable us to get and incredible amount of compression and what we eventually got was about 10 to one.”. “Then we split the game into two games which became Zork I and II.”. Retrieved from the Internet Archive, EFWCG collection, Sep 9, 2015.

The New Zork Times, “The History of Zork – Second in a Series” by Tim Anderson, pgs. 3-5, Spring 1985. “The last puzzle was added in February of ’79.” “…the last mainframe update was created in January of ’81.” Retrieved from the Internet Archive, NZT collection, Sep 24 2015.

Scott, Jason, comp. “Humor Liberation Front Disrupts Meeting.” Status Line Mar. 1986: 2. 28 May 2013. Web. 16 Sept. 2022. Image of Al Vezza and a roomful of lookalikes, 1986

Page 1 – You see a market here.

Zork Retooled for Home Computers

Byte, “Zork and the Future of Computerized Fantasy Simulations” by P David Lebling, pgs. 172 -182, Dec 1980. Retrieved from the Internet Archive, Byte magazine collection

XYZZYnews Home Page

The New Zork Times, “The History of Zork – The Final (?) Chapter: MIT, MDL, ZIL, ZIP” by Stu Galley, pgs. 4-5, Summer 1985. “…they [Joel Berez, Marc Blank] had to work for IOUs, since the company treasury – which started with only $11,500…” Retrieved from the Internet Archive, NZT collection, Sep 24 2015.

Time Magazine, “Computers: Putting Fiction on a Floppy”, by Philip Elmer-Dewitt, Monday Dec 5 1983

Image of Zork history book and map from the Infocom Documentation Project, Manuals, Zork I, retrieved Sep 25 2015.

Page 1 – You find a Zork.

Zork Gets Commercial Release/Sequels to Zork

“Microsoft’s New Consumer Division.” Intelligent Machines Journal 19 Dec. 1979: 7. Print. Microsoft Consumer Products’ initial offering includes…Adventure for the TRS-80 and Apple II…

Creative Computing, “How to Fit a Large Program Into a Small Machine” by Marc S. Blank and S.W. Galley, pgs. 80-87, Jul 1980. “The stripped-down version of MDL that resulted was named Zork Implementation Language (ZIL).” Retrieved from the Internet Archive, Creative Computing collection, Sep 30 2015.

3 prototype versions of Infocom logo. Digital images. Internet Archive. Steve Meretzky/Jason Scott, 25 Nov. 2015. Web. 16 July 2021.

elblanco. (1987, April). Adventuring: Zork I. Atari User, 31–33. Retrieved March 18, 2023. Illustrated map for Zork I

“Infocom Authors – Mike Berlyn.” Infocom Authors – Mike Berlyn. N.p., n.d. Web. 31 Aug. 2016. …which, in 1982, brough Mike’s attention to a job offer from Infocom…

Scott, Jason. Image of Michael Berlyn, circa 2006. Digital image. Get Lamp. Jason Scott, 25 Feb. 2006. Web. 31 Aug. 2016. <http://www.getlamp.com/>.

Barol, Bill. “Zorked Again.” Comp. Tracey Gutierres. Newsweek 23 Dec. 1985: 70. Internet Archive. 31 Aug. 2012. Web. 8 Jan. 2023. With 18 games on the market and four on this week’s authoritative Softsel Hot List – including Zork I, now marking its 169th week in the Top 20…

Sherr, Lynn. “Sally Ride: America’s First Woman in Space.” Sally Ride: America’s First Woman in Space. New York Etc.: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2015. 140. Print. With its shuttle decore and their new Apple III computer – on which they [Sally Ride and husband Steve Hawley] played endless hours of the fantasy game Zork…

Dyer, Richard. “Masters of the Game.” The Boston Globe 06 May 1984: 12+. Newspapers.com. Web. 15 July 2021. Image of Infocom programmers with games, photo by Jerry Berndt. Other info: Astronaut Sally Ride told People magazine that Zork, Infocom’s first game, a fantasy adventure, was driving her to her knees. ;”The way we start here is to write up a treatment, a 10- to 20-page plot outline with events and characters. Then we show it around and work cooperatively.” ;”…that’s when Infocom had two full-time employees and worked out an 8-by-10 office in Faneuil Hall.’ ;He [Marc Blank] does admit that the company goes back to earlier games to correct the problems that players have found in them – Zork is now in its seventy-fifth version.

McClung, M. M. “Is It Fun? An Interview with Infocom’s Michael Berlyn and Marc Blank.” Comp. Jason Scott. SoftSide Sept. 1983: 42+. Internet Archive. 6 Sept. 2011. Web. 17 Feb. 2022. We approach designing games a little differently than many adventure game writers. We try to develop a world where the player can walk around unrestricted in movement and action… It’s especially important in all our games that our worlds be consistent internally. The first thing is to design the rules of the world.

Meretzky, Steve. Softsel Hot List for week of November 19, 1984. Digital image. Internet Archive. 23 Nov. 2015. Web. 17 July 2021.

You feel a package.

Infocom Uses Unique Packaging with Their Games

Addams, Shay. “I Beatles Del Computer.” Comp. Bultro. Computer Games May 1984: 34-36. Internet Archive. 17 Nov. 2016. Web. 5 Jan. 2022. Photos of Infocom programmers, with and without Suspended masks, 1984

Image of Suspended packaging from Computer Fun, “Gnusto Ozmoo” by Randi Hacker, pgs. 30-34, 74, April 1984.

Dyer, Richard. “Masters of the Game.” The Boston Globe 06 May 1984: 12+. Newspapers.com. Web. 15 July 2021. The package items, designed by Giardini/Russell in Watertown, are printed in peculiar colors and on oddly folded paper, so anyone who wants to photocopy them has a problem.

Scott, Jason. “Destruction Orders, For Example.” ASCII by Jason Scott. 09 Sept. 2009. Web. 16 July 2021. Much heavy lifting in design, layout, and verbiage for Infocom was done by a firm called Giardini/Russell, Inc. out of Watertown, Massachusetts. In fact, let’s just make it clear – a lot of what people think of as “infocom” is in fact Giardini/Russell. For example: The Zork logo…and, of course, the verbiage of the advertisements I previously discussed.

Scottithgames, comp. “How Very Novel!” Videogaming and Computer Gaming Illustrated Nov. 1983: 75-76. Internet Archive. 26 May 2013. Web. 9 Sept. 2021. Image of Zork I – III game packaging, The Witness packaging and Deadline packaging

Emery, Gene. “‘Leather Goddesses’ Has Computer Company All Aglow.” The Orlando Sentinel (Reuter Newswire) 18 Dec. 1986: E-19. Newspapers.com. Web. 12 July 2021. Just before a beer and pizza party, programmer Steve Meretzky sneaked into the room, went to the blackboard and added “Leather Goddesses of Phobos” to the list of games the company had already produced. “It got to the point where if you didn’t know what you were going to do next, you would say ‘Leather Goddesses of Phobos.'”

Ceccola, Russ. “Adventures at Infocom.” Commodore Jan. 1988: 70+. Print. An imp usually takes four to six months to design a game. The Creative Services department is responsible for putting together the packaging for all Infocom games. Game designer Steve Meretzky followed people for days with these samples in hand [Of Leather Goddesses of Phobos] urging them to guess what the smells were. An imp designs the game on a mainframe DEC 20 system.

“Infocom Cabinet: Leather Goddesses Of Phobos : Steve Meretzky : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive. Ed. Jason Scott. 23 Nov. 2015. Web. 17 July 2021. Two images of mockups of scratch ‘n sniff card for Leather Goddesses of Phobos

@ablekay47. Final design of scratch ‘n sniff card for Leather Goddesses of Phobos. Digital image. All Sizes | Leather Goddesses of Phobos – Scratch and Sniff Interactive [1988]. Flickr, 28 Mar. 2010. Web. 17 July 2021.

New Zork Times, “InfoNews Roundup: New Packaging”, pg.1, Summer 1984. “We believe that we have created the most innovative package in the industry. Measuring 9″ by 7″ by 1″…” “The package opens like a book…” Retrieved from the Internet Archive, NZT collection, Sep 23 2015.

Image of Marc Blank and Joel Berez together from MicroAdventurer, “Meet the men behind Infocom’s mask”, by Andrew Briggs, pgs. 10-11, Nov 1983

Dyer, Richard. “Masters of the Game.” The Boston Globe 06 May 1984: 12+. Newspapers.com. Web. 15 July 2021. 1984 image of Joel Berez at striped table, photo by Jerry Berndt

Image of Suspended packaging from Computer Fun, “Gnusto Ozmoo” by Randi Hacker, pgs. 30-34, 74, April 1984.

Colour Zork poster by David Ardito, copyright Zork Users Group. Retrieved from /vr/ – Retro Games, “Old School Game Art” by Anonymous, Sept 23 2015.

Bultro, comp. “De Två Stora Nyheterna – Här är Dom!” Joystick (Sweden) Jan. 1985: 14. Internet Archive. 13 June 2019. Web. 15 Apr. 2021. Image of packaging from Suspect

“Commodore C64 Manual: Suspended (1983)(Infocom) : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive. Ed. Jason Scott. 23 May 2013. Web. 18 July 2021. Photo of Suspended ‘feelies’

Page 1 – You find a clue.

The Zork User’s Group

Image of Mike Dombrook, and other information from Electronic Games, “The Challenge of Zork” by Tracie Forman, pgs. 54-57, Mar 1984. Retrieved from the Internet Archive, Electronic Games magazine collection.

Meretzky, Steve. “Video Game Instruction Book:InvisiClues for Zork: The Great Underground Empire, Part I – Google Arts & Culture.” Google. The Strong National Museum of Play. Web. 17 July 2021. Image of cover from first ZUG book, for Zork

“Hotline: Consumer Beat.” Electronic Games July 1984: 14. Electronic Games – Volume 02 Number 13 (1984-07)(Reese Communications)(US). Internet Archive. Web. 09 Feb. 2016. Image of The Witness InvisiClues booklet

Computer Gaming World, “Hobby & Industry News”, pg. 4, Oct 1983

The New Zork Times, “Meet the Zork Users Group”, pg. 3, Summer 1983. “Mike started the Zork Users Group in October of 1981. He had been working at the MIT Lab for Computer Science and part-time for Infocom as the game-tester (their first paid employee).” “In September 1981, Mike left Cambridge to attend the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business” Retrieved from the Internet Archive, NZT collection, Sep 22 2015.

Van Gelder, Lindsy. “In Search of the Exotic: New Directions in Adventure Games.” PC Magazine, July 1983, pp. 345–351. Dornbrook knew nothing about computer games… and when Blank was beta-testing the Zorks, he called his old friend to give him an unbiased perspective.”They originally paid me 6$ an hour,” Dornbrook says, “I fell in love with the games, but I didn’t tell them, because I thought they wouldn’t pay me anymore.”

The New Zork Times, “Zork Users Group Will Shut Down”, pg. 1, Summer 1983. “…Mike, the founder of the Zork Users Group, is getting his M.B.A. in June and going to work for Infocom in August as product manager for entertainment products.” Retrieved from the Internet Archive, NZT collection, Sep 22 2015.

Ceccola, Russ. “Adventures at Infocom.” Commodore Jan. 1988: 70+. Print. Director of Marketing Mike Dornbrook was the company’s first tester.

The New Zork Times, “More InvisiClues”, pg. 1, Fall 1982. “The InvisiClues booklet for Zork I includes over 175 hints (and answers) to over 75 questions…” Retrieved from the Internet Archive, The New Zork Times collection, Sep 22 2015.

Dyer, Richard. “Masters of the Game.” The Boston Globe 06 May 1984: 12+. Newspapers.com. Web. 15 July 2021. Image of Mike Dornbrook holding an Infocom ad, photo by Jerry Berndt. Other info: “By the time that [ZUG] was absorbed by Infocom, there were 20,000 members, and four employees were filling 1000 orders a week for the game, the T-shirts, and the ‘I’d Rather be Zorking’ bumper stickers.”

Infocom, Inc. “Our Circuits, Ourselves!” Cambridge, MA: Infocom, 1983. Internet Archive. 19 Oct. 2014. Web. 16 July 2021. Image of Deadline InvisiClues book.

“How Can I Get a Babel Fish?” InvisiClues: The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Cambridge, Mass: Infocom, 1984. 12-13. Print. Image of pages from Hitchhiker’s InvisiClues book.

Page 2 – A hoopy frood enters the room.

Douglas Adams and the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Game

Adams, Roe R., III. “The Infinitely Improbable Doug Adams.” Electronic Games Apr. 1985: 22+. Electronic Games – Volume 03 Number 04 (1985-04)(Reese Communications)(US). Internet Archive. Web. 10 Feb. 2016.

Meretzky, Steve. Early snapshot Image of Steve Meretzky. Digital image. Infocom Cabinet: Meretzky Photos. Internet Archive, 23 Nov. 2015. Web. 18 July 2021.

“Commodore C64 Manual: Stationfall (1987)(Infocom) : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive. Ed. Jason Scott. 23 May 2013. Web. 18 July 2021. Photos of Stationfall ‘feelies’ and Stellar Patrol patch in particular

Infocom. PR. Profile on Steve Meretzky. Cambridge, Mart: Infocom, 1983. Print. Writing interactive fiction was evidently a good career change for meretzky, who earned a degree in Construction Project Management from M.I.T. After graduation, he took three successive jobs in his field. None of them provided the satisfaction he’d anticipated. In mid-1981, he was out of work and spending a lot of time around the apartment he shared with Michael Dornbrook… ;At the time, Dornbrook was testing Zork I and Zork II for Infocom. Meretzky began to play the games, reporting bugs when he found them. He did such a good job…..Infocom’s Marc Blank needed someone to test Deadline, he though of Meretzky. By June 1982, Steve Meretzky was working half-time as a game tester at Infocom. he began work on Planetfall, spending less time testing and more time writing. In October 1982, he began full-time work as an Infocom game writer. Planetfall was released in September 1983.

Scott, Jason, comp. “Cover.” Softline Sept.-Oct. 1983: 0. Internet Archive. 18 Mar. 2017. Web. 21 Jan. 2023. Image of the cover of Softline magazine featuring Floyd’s death sequence from Planetfall, by Steve Meretzky

Addams, Shay. “Wander Into Wonderland!” Comp. Jason Scott. Family Computing June 1985: 40. Internet Archive. 23 Nov. 2015. Web. 17 July 2021. When I was doing Hitchhiker, I phoned around all the English bulletin boards to see what the level of awareness of Infocom was. It was very strong, but amongst a fanatical minority.

Young, J. S. (1985, May). A Hitchhiker’s Guide to Douglas Adams. MacWorld, 148-153. Images of Douglas Adams standing next to pole, laid out with guitar and reading the newspaper. Photos by Barbara Ries

Black & white image of Meretzky and Adams together from the New Zork Times, “The History of Zork – First in a Series” by Tim Anderson, pgs. 7, 11, Winter 1985. This photo and a different pose of the two in colour from a different source, by Ralph Mercer. B&W photo retrieved from the Internet Archive, NZT collection, Sep 23 2015.

Addams, Shay. “Wander Into Wonderland!” Comp. Jason Scott. Family Computing June 1985: 40. Internet Archive. 30 Aug. 2011. Web. 12 Apr. 2020. From interview with Douglas Adams [Answering question “What was the first adventure game you played?”] Original Adventure… on The Source about a year-and-a-half ago while living in Los Angeles. I guess my first commercial game was Suspended. That was the only one I actually played to the bitter end and completely finished. I played Deadline and Zork I and Starcross about the same time, but never finished them.

In fact, Douglas’ first introduction to Infocom was through playing Suspended, one of the company’s most mind-boggling games. (Yes, he solved it.) It occurred to him that here was a company with minds as devious and eccentric as his own.; Another creative locale was Huntsham Court, a hotel in the village of Huntsham, near Tiverton, Devon. Adams wrote So Long and Thanks for all the Fish there, and a lot of the electronic version of Hitchhiker’s as well.; Image of Douglas Adams with his thumb out.

Infocom. PR. Douglas Adams and Steve Meretzky: A Best Selling Combination. Cambridge, Mart: Infocom, 1984. Print. As the project moved forward, telecommunications played a key role. Adams and Meretzky were able to communication between Cambridge, Mart and Adams’ home in England by means of modems hooked up to DEC Rainbow computers. Says Meretzky, “Doug would write detailed ‘chunks’ of material and send them by modem. I’d transcribe the material directly onto a disk in my computer. In the same way, I would send Doug portions of the game as programming was completed.” ;”In June, I travelled to Europe to work with Doug on the final design.”

Darling, Sharon. “Douglas Adams and Steve Meretzky: Designers Behind The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy.” Comp. Jason Scott. Compute!’s Gazette Apr. 1985: 42-47. Internet Archive. 23 Nov. 2015. Web. 17 July 2021. During the writing process, Meretzky says he tried to closely emulate Adams’ style. Apparently, he succeeded, as Adams commented once that he couldn’t tell whether he or Meretzky had written certain parts of the text.

Zenko, Darren. “Hitchhiker’s Guide Is Back to Remind Gamers How Words Can Spell Adventure.” Edmonton Journal 04 Mar. 2005: E11. Newspapers.com. Web. 13 July 2021. Selling 350,000 copies in ’84, the Guide game was a commercial and critical success…

Schultz, Monte, and Steven Arrants. “Infocom Does It Again…And Again.” Review. Creative Computing Dec. 1983: 120-23. Print. Image of Planetfall packaging

Ceccola, Russ. “Adventures at Infocom.” Commodore Jan. 1988: 70+. Print. Steve Meretzky…started out as a tester with the company…

Miller, Stephen. “Popular Novels Find New Home on Computers.” Arizona Republic 30 Nov. 1984: G. Newspapers.com. Web. 13 July 2021. “I was a big fan of Doug’s, ” Meretzky said, “and when they asked me if I wanted to work with him, I took a long time saying yes; maybe two or three seconds.”

Antic, “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” review, by Jack Powell and Michael Ciraolo, pg. 19, May 1985

Adams, Douglas. “Douglas Adams Is the Bestselling Author…” Introduction. Mostly Harmless. London: Heinemann, 1992. Print. Dust jacket image, photographer unknown

“Douglas Adams Is the Best-selling Author….” Introduction. The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul. Toronto: Stoddart, 1988. Print. Profile image of Douglas Adams, 1988. Photo by Jill Furmonovsky

Scott, Jason, and Steve Meretzky. Headshot of Steve Meretzky. Digital image. Internet Archive. 23 Nov. 2015. Web. 17 July 2021.

Scott, Jason, and Steve Meretzky. Product shot of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy feelies. Digital image. Infocom Cabinet: Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Internet Archive, 23 Nov. 2015. Web. 17 July 2021.

New Zork Times, “Don’t Stick This in Your Ear”, pg. 1, Sprint 1985. “Now there’s a safer, more socially acceptable way to show your excitement about Hitchhiker’s, with an official Infocom “I GOT THE BABEL FISH” t-shirt.” Retrieved from the Internet Archive, NZT collection, Sep 24 2015.

Scott, Jason, comp. “Hitchhiker’s Doug Adams Takes Us to His Galaxy.” Electronic Games Apr. 1985: Cover. 28 May 2013. Web. 17 July 2021. Douglas Adams on the cover of Electronic Games

“News.” Computer Gamer, Sept. 1985, pp. 4–4. Image of Douglas Adams holding a towel

Page 2 – NEXT WINDOW PLEASE

Bureaucracy Text Adventure by Douglas Adams and Infocom

Scott, Jason, comp. Bureaucracy Instruction Manual. Cambridge, MA: Infocom, 1987. Print. Photo of Bureaucracy ‘feelies’.

Page 2 – This passage leads to a dead end.

Zork Follow Ups/Infocom Bought by Activision

Cornerstone announcement date from Don Thomas’ I.C. When history timeline: http://www.l4software.com/icwhen

Levine, Martin. “Home Software Firms Exploring the Office.” Newsday (Nassau Edition) [Hempstead, New York] 01 July 1985: 3 / Part III. Newspapers.com. Web. 14 July 2021. Infocom is aided by the fact that five of the top software distributors in the county….agreed to carry the program even before it was released.

Ruiz, Frank. “Software Sellers Tap into Mind Games.” The Tampa Tribune 15 Nov. 1987: 9-E. Newspapers.com. Web. 14 July 2021. The program, called Cornerstone, sold about 10,000 copies.

Cover of Cornerstone database program. Digital image. Infocom Cabinet: Mixed Bag: Infocom. Jason Scott, 25 Nov. 2015. Web. 16 July 2021.

Adams, Jane Meredith. “Calif. Company Buys Infocom.” The Boston Globe 21 Feb. 1986: 75. Newspapers.com. Web. 14 July 2021. After the acquisition, chairman Al Vesa [sic] “is not staying with the company,” according to Berez, a 1976 MIT graduate who already has taken over Vesa’s [sic] role as chief executive officer.

The Status Line (ne: The New Zork Times), “Infocom Weds Activision”, pg. 1, Spring 1986. “On February 19, 1986, Activision, Inc. announced that Infocom would be purchased by Activision, in a transaction valued at approximately $7.5 million. ” “…the newly merged couple will maintain their separate product development and marketing facilities in Mountain View, CA, and Cambridge, MA.” Retrieved from the Internet Archive, NZT collection, Sep 24, 2015.

Scott, Jason, comp. “Infocompeition.” Games Machine Oct. 1987: 44-45. Internet Archive. 8 Apr. 2012. Web. 1 Aug. 2021. Image of a large collection of Infocom games, 1987

Rosenberg, Ronald. “Computer-games Firm Moving to California.” The Boston Globe 22 May 1989: 8. Newspapers.com. Web. 14 July 2021. Infocom Inc.,…is closing its doors in Cambridge and moving to Menlo Park, Calif., next month. ;The relocation is a cost-saving measure, since Infocom has been losing an average of $200,000 per fiscal quarter for the past two years, according to Laura L. Stagnitto, Mediagenic’s director of corporate communications. ;She said 11 of the remaining 26 Infocom employees were offered a chance to move to California, but only five have accepted, including Joseph Ybarra, president. He will become vice president of Mediagenic’s entertainment division. ;Berez resigned last summer…

Ceccola, Russ. “The Winter CES of Our Discontent.” Questbusters, X, no. 2f, Feb. 1993, p. 1.

All the characters in Return to Zork are digitized, and it includes a lot of video (they took over 20 hours of footage, much of which will make it into the CD version). Activision employed professional actors and actresses and made a major production out of Return to Zork.

“What’s the Future of Online Gaming?” Next Generation, July 1996, pp. 6–10. 1996 image of Brian Moriarty in front of a server rack

Infocom, Inc. Infocom’s New Graphics Will Blow You Out of the Water… Cambridge, MA: Infocom, 1989. Internet Archive. 8 Aug. 2022. Web. 28 Jan. 2023. Brochure cover, pages for James Clavell’s Shogun, Journey and Quarterstaff.

Plundered Hearts Instruction Manual. Cambridge, MA: Infocom, 1987. Print. Image of velvet purse included in game

Infocom

Image of Infocom booth at 1985 COMDEX from the New Zork Times, “InfoNews Roundup”, pg. 9, Winter 1985. Retrieved from the Internet Archive, NZT collection, Sep 24 2015.

“Zork Trilogy (1983) Box Cover Art.” MobyGames. Ed. Jon De Ojeda. 07 Mar. 2003. Web. 18 July 2021.

“Enchanter Trilogy (1986) Box Cover Art.” MobyGames. Ed. Quapil. 23 Sept. 2006. Web. 18 July 2021.

“Classic Text Adventure Masterpieces (1996) Box Cover Art.” MobyGames. Ed. Corn Popper. 13 Dec. 2003. Web. 18 July 2021.

Ceccola, Russ. “64 and 128 Software Reviews: Beyond Zork.” Commodore May 1988: 22+. Print. Game implementor Brian Moriarty remarked, “The reason for the interface is to use the full power of the machine as well as to make Beyond Zork easier to play. Moriarty spent exactly one year and three days in readying Beyond Zork for a discrimination world.

Box shot Return to Zork (Box shot – Front) | Abandonia – www.abandonia.com/en/boxshot/24295

“Infocom The Adventure Collection 1995 Jewel Case Art : Infocom : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive. Ed. IceTeaMan. 29 May 2013. Web. 18 July 2021.

“Infocom The Comedy Collection 1995 Jewel Case Art : Infocom : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive. Ed. IceTeaMan. 29 May 2013. Web. 18 July 2021.

“Infocom The Fantasy Collection 1995 Jewel Case Art : Infocom : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive. Ed. IceTeaMan. 29 May 2013. Web. 18 July 2021.

“Infocom The Mystery Collection 1995 Jewel Case Art : Infocom : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive. Ed. IceTeaMan. 29 May 2013. Web. 18 July 2021.

Unannotated, Uncategorized or I Just Don’t Damn Remember!

Mobygames

Ye Olde Infocomme Shoppe

The Interactive Fiction Archive

Faye’s Shrine of Zork

External Links (Click to view)