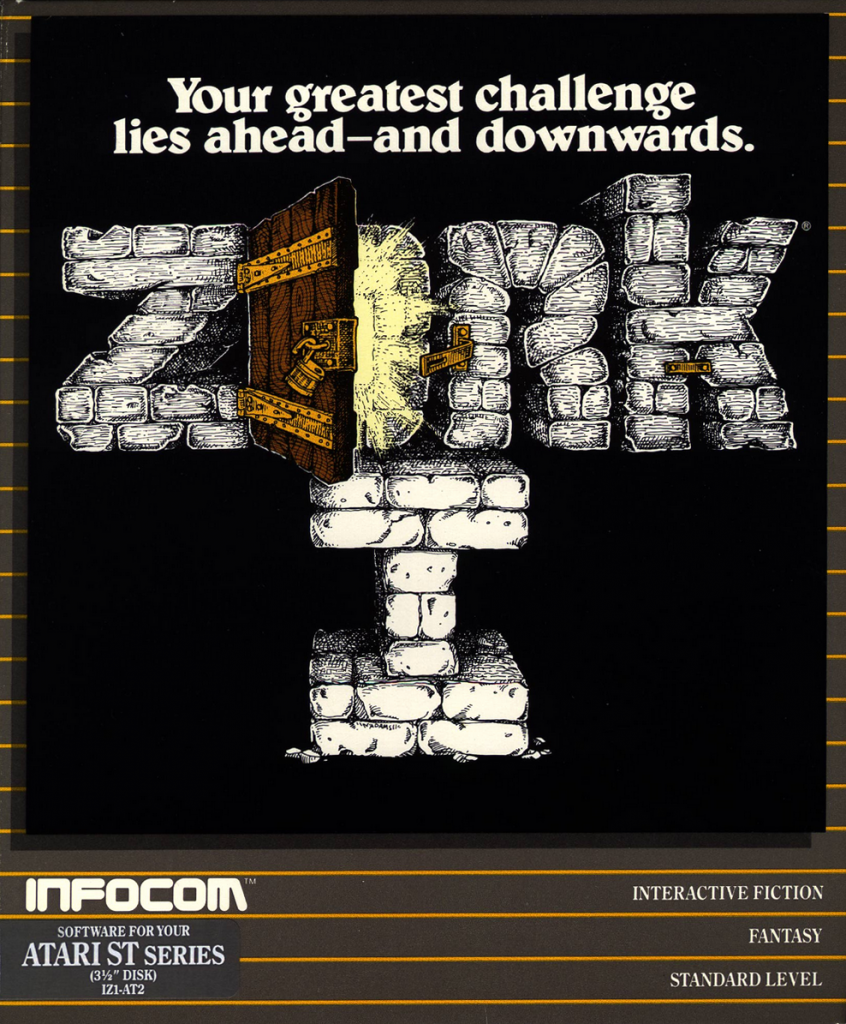

Woe to the poor gamer who slid the floppy for Infocom’s computer adventure game adaptation of Douglas Adams’ seminal book The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy into their unsuspecting drive. Not because it was a bad game; it wasn’t. Unless you mean bad as evil. Then it was very, very bad, indeed.

Adams was an early technophile, quickly falling in love with the Apple II, and subsequently with Apple’s revolutionary Macintosh computer. He was also fond of Infocom’s adventure games, and signed a multi-game deal with the company in early 1984. Paired with famed Infocom game implementer Steve Meretzky, the two banged out the Hitchhiker’s game over a six month period; Adams writing passages in England and emailing them to Meretzky in Cambridge, MA. Meretzky ended up having to chase famous procrastinator Adams down to a remote British resort to finish work on the game.

Upon release in late 1984, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was a huge hit, moving over a quarter of a million copies. Breaking many cardinal rules then established in interactive fiction, it also caused a million hairs to be pulled out by frustrated gamers. Transgressions included outright lying to the player about available directions to travel in, and even what the player was able to see. It also often required players to have read the book to know what to do in certain situations. Perhaps worst of all, a favourite torture of Adams was to let you miss some critical piece of equipment during a scene that would cause the game to dead-end later, with no recourse but to reload a save or replay the game. At times it seemed that Hitchhiker’s was purposefully created as a ploy by Infocom to sell more of their Invisiclue hint books.

These brutalities aside, Hitchhiker’s is still an entertaining and interactive excursion through one of the greatest science fiction comedies of all time.

For more information on Hitchhiker’s and Infocom, consult your local Dot Eaters Bitstory.